By Marcin Wojtyczka

80 minutes readCollection of procedures to use on a sailing boat.

Most problems on a boat can be avoided with proper planning and regular maintenance. However, unexpected events can still occur. That’s why it’s essential to invest time in planning for contingencies and making basic preparations before heading out to sea.

Your first response may not resolve the problem or be perfect, but persistence is the key. You must keep trying until you find a solution. Always think ahead and plan for contingencies. Ask yourself: What’s our fallback if the wind shifts, making this anchorage or dock unsafe? Which docking approach offers the best options for departure? If the engine fails, which sails should we deploy to maneuver safely?

The procedures presented here are based on personal experiences and the collective wisdom of other sailors. They were created for sailing vessels less than 24m in length in mind. They will largely be applicable to larger vessels as well. However, you should adapt them based on your specific situation, conditions, vessel, and crew availability.

Certain actions are universally applicable to nearly all emergency situations. These are outlined below to avoid repetition in each specific scenario:

- Sound general emergency signal.

- Muster the crew (headcount).

- Stop engines or slow down.

- Close watertight and fire doors if available.

- Assess the extent of damage.

- Check for any other issues (fire, explosion, pollution – ex. Leaking oil).

- Decide if watertight integrity is compromised (are you going to sink), check stability booklet if available.

- Verify position of the vessel and navigation hazards in vicinity.

- Check weather and tide forecasts. Determine if the weather or tide is carrying the vessel into more danger (use anchors if necessary).

- Implement control measures (fix).

- Display appropriate lights and day shapes.

- Inform VTS or ships in the area.

- Modify AIS status if applicable.

- Send distress / urgency message.

- Consider abandoning ship if required, or beaching the vessel.

- Report to shore as appropriate, e.g. MAIB, DPA, port and flag state, class, insurance company.

- Debrief to improve safety after the accident.

Man overboard

You should practice the procedure regularly with the crew but remember that your first and foremost priority should be to prevent it.

Prevention:

- Keep one hand for yourself, one hand for the shop.

- Ensure steady footing.

- Wear a life jacket and clip-on tether (lifeline) to a secure attachment point or a jackstay (in bad weather, at night, and whenever you feel unstable or want to).

- Don’t drink alcohol en route and be sober before you set out.

- Don’t dangle off the backstay or head for the leeward shrouds to have a pee, use heads.

Steps:

- Shout “Man Overboard”.

- If running with the engine, stop the prop and turn toward the side the MOB went over to not run over him.

- Press the MOB button on the GPS and check that you have a track running.

- Toss buoyancy (e.g. lifering) and dan buoy.

- The person spotting the MOB point in the direction of the MOB until releaved. Post additional lookouts with binoculars.

- Immediately disengage the autopilot and heave-to to keep close to the MOB:Before making the turn alert everyone to hold on.Tack the boat without releasing the headsail (the boat should remain almost in position with the headsail backed on the wrong side).

- Check there are no lines overboard and start the engine.

- Approach as if you were motor boat by executing crash stop, Williamson turn, Anderson turn or similar. Otherwise, if the engine cannot be started, execute figure 8 method if you are far away from the causality and not drifting towards it.

- In the meantime, transmit Distress/Mayday on VHF / MF / HF / Inmarsat depending on your area.

- Make a recovery decision and prepare recovery equipment.

Final approach and retrieving:

- Drop the foresail(s).

- If the MOB is conscious, approach the MOB upwind (1-2 boat lengths) and toss a retrieving line (lifesling or floating heaving line with a bowline). Watch out for any lines in the water and disengage the propeller when in doubt. If under sails, approach with the mainsail and control the speed using the spill and fill method (let the main out until it depowers and then before you lose all way, pull it back again in to maintain steerage).

- If the MOB is unconscious launch a tender/dinghy or liferaft to create intermediate platform.

- Recover the MOB: pull the retrieving line to bring the MOB to the boat, tie a loop on the line (3-4 m up from the mob), attach a halyard to the loop and lift the mob onboard. A horizontal lift is preferred to avoid secondary drowning and cardiac arrest. In real life it’s very difficult to do. The simplest method might be to put a line around legs and have someone pull that line as you winch the person up to make sure the position is more horizontal.

- Apply first aid if required and call MRCC for medical advice.

- Consult IAMSAR Manual Volume III for more info.

If you enter the water unexpectedly:

- Take a minute. The initial effects of cold-water pass in less than a minute so don’t try to swim straight away.

- Try to relax and float on your back to catch your breath.

- Try to get hold of something that will help you float.

- Keep calm then call for help or swim for safety if you’re able to.

If you cannot find the causality in the water after the rescue maneuver:

Execute search pattern:

- Sector search to search relatively small circular area (witnessed causality)

- Expanding square search or creeping line if you don’t know exactly when causality went over (unwitnessed causality)

MOB and prevention methods are described in great detail in this article..

Abandoning ship

The decision to abandon a ship is usually very difficult. In some instances, people have perished in their liferaft while their abandoned vessels managed to stay afloat. Other cases indicate that people waited too long to successfully get clear of a floundering boat.

Abandoning a ship should only be considered if your boat sinks or catches fire that cannot be controlled. Do not leave the yacht until it leaves you! Stay on board if there is no grave danger. Even a battered, damaged yacht will be a better shelter than a rubber raft.

Steps:

- (Captain) Announce abandoning the ship by voice.

- All crew to put on all available waterproof clothing, don lifejackets and safety harnesses.

- All crew mustered.

- Nominated person sends Mayday (DSC + R/T on VHF/MF/HF and/or Sat Com) and note present position.

- Nominated person collect Grab Bags.

- Nominated person collects collects additional items from the boat, e.g. food, water, clothing etc.

- Nominated crew deploy liferaft:prepare(s) for deployment (bring it on deck and secure the painter).deploy it to leeward/downwind (unless ship on fire).throw the liferaft overboard and pull the painter, kick sharply upon resistance.

- Nominated persons launch the dinghy/tender and attach it to the liferaft (if time allows).

Primary actions:

- All crew to enter the liferaft and pass grab bags. Step into the liferaft, do not jump. If impossible to step into, secure yourself to the painter with a tether and swim to the liferaft.

- Check the presence of all crew and grab bags. Look for survivors if necessary.

- Keep liferaft tethered to vessel as long as possible. Only cut the painter when the boat is actually sinking or there is a risk of explosion. Cut the painer with a knife attached to the liferaft as closest to the ship as possible.

- Manoeuvre clear from the ship.

- Reduce the rate of drift by deploying drogues. Remaining as close as possible to the mother ship and the position indicated in Mayday message will significantly aid rescue services in locating you promptly.

- Keep interior of the liferaft out of water (sea or rain) and wind by closing up entrances.

- Check for damage. Repair or plug if necessary.

- Insulation - Inflate the floor of the raft.

- Check position of inflation (topping up) valves.

- Install radar reflector.

- Allow natural body heat of survivors to warm interior air. When warm and atmosphere is heavy and uncomfortable, adjust ventilation. A very small opening should be sufficient.

Secondary actions:

- Activate EPIRB (attach to a person or liferaft and put into the water to avoid strobe light and get better connection with the satellite).

- Activate SART Radar/AIS if vessels are expected in vicinity.

- Take seasickness pills. Life rafts are known to make even the best sailors seasick. Seasickness is not only a physical handicap, but valuable body fluid may be lost. The pills themselves will make your mouth feel dry but resist the urge to drink.

- Treat injured crew. Maintain a clear airway and control any bleeding. The quiet people will likely have health issues. The loud ones are likely be ok.

- Bail out. Remove any water with bailer and dry out with sponges.

- Post lookouts for to look for survivors and other ships, collect debris etc. Assist survivors by using the quoit and line, thereby avoiding swimming. Raft may be maneuvered using drogue or paddle. Arrange for collecting rainwater.

- Warming up. If people are chilled or shivering, get everybody to huddle together. Cover with spare clothing. Sit on lifejackets as extra insulation if necessary. Loosen any constriction on feet. Keep wriggling toes and ankles to reduce chance of getting cold injuries. Change lookouts if necessary to prevent frostbite on exposed skin.

- Make a large target. Join up and secure if there are other craft in vicinity - mutual aid. In cold weather, get maximum numbers together for warmth. Two or more craft are easier to find than one.

- Use VHF and other means of communication (e.g. sat com) and follow the distress procedure.

- Ration water, after 24h, to a maximum of half-litre per person per day, issued in small increments. Do not drink seawater or urine, this will only make you sick.

- Use flares only when there is a real chance of being seen.

- Keep morale and will to survive. Cold, anxiety, hunger, thirst, effects of seasickness all work against the will to survive. Keep spirits up. Maintain confidence in rescue.

- Fishing is fine but you need plenty of water to digest the proteins. Fishing with hooks is also problematic on rubber boats.

- Read the survival craft handbook for further guidance on actions to be taken etc.

The fact that on a cruising vessel, there may be only two people on board does not invalidate the necessity to have the responsibilities clearly defined. A suggested sample of this is presented above, with the two crew shown as A and B.

Fire

Fire is an infrequent but terrifying occurrence on board a boat. Because of the environment and potential distances involved, firefighting assistance may take a while to arrive on the scene. Plus, unlike fires on shore, there may be no place to evacuate except into the water. It is important to make every effort to prevent fires. There are many potential causes of fire on board. Fire damage caused by flammable gases in the engine compartment is particularly common. Engine compartments on ships are usually closed systems, and vapours can quickly collect and compress here. Mixed with oxygen, a highly ignitable gas mixture can be formed.

Prevention:

- Inspect the electrical system regularly (the source of most boat fires).

- Don’t overload power sockets.

- Don’t use cheap chargers and don’t leave chargers in power sockets when not in use.

- Don’t leave running stove unattended.

- A clean boat is a safe boat:Clean up grease from the galley.Empty wastepaper baskets regularly (control the garbage).Remove combustible materials near heat sources (e.g. not hanging clothes over cooker or heater).Use steel bins for oily waste in the engine room.Store and use items such as cleaning fluids, paints, solvents, aerosols and other highly flammable material as directed by the manufacturer. Secure them properly.Keep electrical and mechanical areas clean and away from objects that could interfere with normal systems. This includes cleaning up any spilt oil (engine compartment, stove) or fuel.

- If you have gas onboard, turn it off as close to the source as possible. Make sure the gas storage area is vented and your saloon is fitted with a gas alarm serviced regularly. If gasoline or propane leaks into the bilge, the boat is a floating bomb ready to explode when the engine is started.

- Check for wear, damage, and leaks in burners, hoses, fittings, blowers and vents. A boat with a gasoline engine must have a bilge blower: one with a diesel engine should have one.

- Fit an automatic fire extinguisher system in the engine compartment, one large portable extinguisher near the stove and several portable extinguishers in living areas.

- Keep extinguishers charged and have them inspected as per the label. Twice a year turn the extinguishers upside down and shake them to loosen dry chemical.

- Don’t smoke onboard. If you must, make sure it’s on deck away from flammable items.

- Check and maintain all fire control equipment regularly (see IMO guidelines here).

- Make sure that the crew can escape from any part of the boat (e.g. a dinghy on the foredeck can make fast exit impossible).

- When performing maintenance tasks involving heat, such as welding or grinding, implement fire prevention measures.

- Perform regular drills for the crew (once per month) or when more than 25% of the crew is changed.

- Fit smoke detectors with alarms.

- Make routine maintenance on your drenching, sprinkling or high fog systems (bigger vessels).

Steps:

FIRE: Find, Inform, Restrict, Extinguish or Escape

- Shout “Fire Fire Fire” and the location.

- Discover what is burning, and also the seat of the fire.

- Tackle the fire immediately if possible by using nearest extinguisher, buckets of seawater (never on electrical or oil fire), or with a fire blanket (galley), otherwise escape to the agreed muster location, closing all door on the way out.Pull the fire extinguisher pin, aim at the base of the fire, squeeze the trigger, and sweep the fire with a side-to-side motion. Aim well. You will only have 10-30 seconds before the extinguisher is discharged.Fires can double in size in less than 10 seconds, two minutes may well be the maximum time you have to put out a fire before it spreads through the boat. It’s not just the flames you should worry about. Older foam cushions give off hydrogen cyanide when burning – just a single lungful can kill. The quantity of the extinguishing agent is everything – a 2kg extinguisher will be twice as effective as 1kg so use everything you have available. Empty the entire content of the extinguisher in order to reduce the risk of reignition. If anyone on board has had any training then the likelihood of success is far greater.If the engine does not have an automatic extinguishing system (usually CO2), try and discharge extinguishers into the engine space through a dedicated fireport, vent or hole. Do not open up the engine space.

- Ring Alarm Bells if necessary (continuous ringing).

- Muster crew and guests on deck whilst also allocating crew to extinguish the fire. Move to the windward side to avoid the smoke.

- Rescue people who may be trapped inside the boat. Keep as low as possible to stay away from dangerous smoke and heat. If someone’s clothes are on fire, help them get on the deck and roll them on the floor to keep flames away from face. Use a blanket to press out the fire, starting from the head.

- Stifle the fire by shutting down the ventilation system, air conditioning, fire flaps, skylights, all doors, portholes, scuppers etc.

- Depending on fire location, close shut off fuel valves, gas bottles and electricity. You may want to throw all gas cylinders into the sea to avoid an explosion.

- Steer downwind course to reduce air flow over the deck (reduce apparent wind), unless dense smoke is hampering operations.

- Apply boundary cooling (cool down compartments on fire from six sides) to avoid the heat from spreading to the rest of the boat.

- Spray or flood any adjacent magazines containing dangerous goods.

- Remove any surrounding materials which are in danger of igniting.

- While some crew members fight the fire, others should be preparing to abandon the ship.

- Call for help using any means: VHF CH 16 (Mayday), phone etc. Call the fire brigade if the fire happens on the dock.

- Fix position and consider weather. Consider boat’s stability and pumping arrangements, if water is being used.

- Spray all adjacent bulkheads and goods.

- Always ensure the safety of the firefighters. For example, discover whether dangerous gases are present and equip firefighters with breathing apparatus (boats > 24m). Always have a spare breathing apparatus available outside the fire zone, for rescue work.

- Watch for any complications that may arise.

- Continually watch for signs of the fire spreading.

- Consider outbreaks of electrical fires.

- After the fire is extinguished, carefully inspect the entire boat for embers at least twice.

- If the fire cannot be contained, abandon the ship.

Initial actions / measures to respond for fire on board:

The specific actions will depend on the vessel, location and situation.

Person who first finds the fire:

- Raise the Alarm/inform bridge

- Discover what is burning and If possible tackle fire immediately

Officer of the Watch:

- Raise the Fire signal

- Call the Master/Skipper

- Slow down

- Fix position

- Close fire and watertight doors

- Shutdown ventilation

- Wait for Master/Skipper to take CON (charge)

Master / Skipper:

- Take the CON of the vessel following full report from OOW

- Muster the crew and passengers and check for casualties (head count)

- Organise fire fighting activities, boundary cooling to be started

- Fuel shut offs

- Activation of fixed fire systems when required (CO2 / sprinkler / high-fog, drenching systems)

- Communications with outside world (Mayday or Urgency)

- Consider weather and stability criteria as appropriate

Follow up actions:

- Record keeping (e.g. pictures, logbook, everything documented and put back in order)

- Assess vessel for structural damage and watertight integrity (stability)

- If required, consider abandoning ship, salvage or towing

- Inform the MAIB and Flag state as appropriate

Flooding / Water ingress

Prevention is the best cure so make proper and regular monitoring of important components. This Pantaenius article describes this in detail.

Prevention:

- Check regularly: water-bearing fittings (hoses, clamps and valves, logger and sonar) - porous hoses and corroded clamps should be replaced, and the clamps should be tightened from time to time.

- The propeller and rudder axle seals are other openings straight into the sea. Find out how to service them and what the seal is made from: grease, oil or mechanical seals all need different type of care.

- Mount anti-siphon valves for bilge pumps and toilets to prevent water coming back into the boat if its outlet is underwater when sailing.

- Close seawater valves when you leave the boat in the marina.

- Lash tapered soft-wood plugs (bunks) to through-hull fittings, pipes and seacocks. In an emergency, you can drive the tapered end to plug a leak.

- Prepare the boat safety diagram to refresh your memory about where all through hulls are and check them.

- Have at least two big manual pumps (ideally diaphragm-type) and one movable.

- Keep spare material for makeshift repairs on board in an emergency (e.g. pre-drilled peice of plywood, epoxy, plugs etc.)

Steps:

- Muster crew with lifejackets.

- Assess the extent of the flooding, and consult stability book if available.

- Start bilge pumps and check auxiliary pumps for backup operation if needed.

- If necessary, use other means:Buckets, bailers, sponges, heads. A scared person with a bucket is the most efficient.You can also try to use a freshwater pump alongside the bilge pump. Keep the bilge free of small objects that might clog the pumps.It’s unlikely you would be able to do this but if the engine is running you could use it as a very big pump. You can disconnect the raw cooling water intake of the engine and take the water hose from the through hull to empty the water. Be sure to check there is no debris that could hinder the water flow to the engine or it may overheat.

- Check if you are dealing with fresh or salt water (salt water usually indicates leakage in the hull, loose keel bolts, or leakage of the propeller shaft flange through stuffing boxes – they should leak only very slightly).

- Turn off all non-essential taps and valves (heads, restrooms, wash basins, water tank).

- Cut off all electrical power running through affected area.

- Immediately start locating the source of the leak and investigate damage, and initiate control measures including environmental impact.

- Establish position and depth and nearest safe port or anchorage etc.

- Check weather and tide forecasts.

- Check stability book if available for damage stability.

- Broadcast URGENCY or DISTRESS message, if appropriate.

- If the hull is holed, heel it as far as you can in the other direction while preparing a patch.

- If the leak is small pump the bilges on a regular, frequent schedule so as not to be caught by surprise by a new leak. Keep track of regular log entries.

- If the water is coming through the deck, check the partners (the deck hole around the mast), window frames, and fastening for deck fittings, such as cleats.

- Plug the leak if possible. Depending on the hole size and location different methods might work:Lessen the water’s pressure on the breach by pushing something on to the breach – a cushion in a plastic bag, sail in a bag, sleeping bag, blanket, duffel bag with clothes held in place by a foot will work on a smaller crack to greatly reduce water ingress.Meanwhile, prepare a better fix: tapered plug, multipurpose waterproof adhesive, repair putty/epoxy, or plywood.You can also try fothering the leak from outside using a sail or collision mat stretched around the hull. The water pressure will help pushing it into the crack. A foil space blanket with tennis ball (or socks) can be made into a makeshift collision mat.

- Record all details of the incident including pictures and video evidence and logbooks etc.

- If the water ingress cannot be controlled: consider abandoning ship or grounding/beaching the boat.

- Report to the shore.

Hole in the hull

Being holed below the waterline presents a number of problems in a variety of scenarios, depending on the size and location of the hole. It is possible to save the boat if you respond quickly. Just to give some perspective: a 5 cm hole 30 cm below the waterline will leak 300 litres per minute. A 10 cm hole at the same depth leaks 1100 litres per minute, enough to sink a 30ft yacht in 12 minutes.

- Tack the boat so that the hole is above the waterline (could help if the hole is near the waterline)

Options if you can get to the hole:

- Fothering the hole with whatever you can find to buy more time, e.g. stamp a pillow or cushion.

- Apply underwater epoxy repair kit (very effective).

- Lash plywood board from inside (e.g. engine room hatch with a sound-proofing sponge, floor boards, bunk board, bosuns chair):Screw the board (you might need to drill holes with a manual drill for underwater repair).

- Lash plywood board from outside:Push a loop of line out through the hole from inside the boat (e.g. with a coat hanger) and snag it on deck with boathook (hanging outside the boat not recommended).Insert a line through a pre-drilled board, knotting the end to hold it in place.Haul and tension the line from inside the boat.

Options if you cannot get into the whole:

- Fother a sail or use a purpose-made collision mat (wrapping it around the hull) – difficult to set up.

Porthole/Hatch failure

Breaking portholes or hatches might not flood your boat, but it could make your life on board hard.

Prevention:

- Close hatches on the sea: they can be thrown overboard by running rigging and can flood the boat in rough seas

- Avoid heavy weather if possible. If the vessel is knocked down or rolled it can cause hatches and portholes to be blown out due to wave pressure. The larger the area of the window, the greater the risk of failure particularly for many production vessels constructed from materials that are more susceptible to flexing under pressure

- Lash storm coverings to prevent windows from being compromised, both by heavy seas and loose items on the deck, such as flogging blocks and eyes

Options if it breaks:

- Tack the boat so that the broken porthole is above the waterline

- Lash something against the hole to minimize water ingress and buy more time (e.g. pillows, cushions, smaller sail, sleeping bags, blankets, duffel bags full of clothes)

- Lash plywood board from inside (e.g. engine room hatch with a sound-proofing sponge, floor boards, bunk board, bosuns chair):Drill holes in the hull and screw the board

- Lash plywood board from outside:Insert a line through a pre-drilled board, knotting the end to hold it in placeHaul and tension the line from inside the boat

Engine failure

Many engine failures at sea are caused by lack of maintenance, resulting in filter blockages, engine pump failures, overheating and then breakdown. It is worth remembering that one of the most common reasons for marine rescue service call-outs is for boats running out of fuel.

Prevention

- Keep the engine regularly maintained

- Always do engine checks before setting out

Daily in use:

- Check fuel, and crankcase oil levels (don’t rely 100% on gauges!)

- Look out for oil, fuel and coolant leaks

- Check fresh water coolant level

- Check that discharge of cooling water coming out from the exhaust pipe is rhythmic, and the gas is colourless and almost invisible

Weekly when in use:

- Check drive belts for wear and tightness

- Check gearbox oil level

- Check fuel racor filter for water and dirt. Drain off any contaminants until the fuel in the clear glass bowl is clear

- Check for water or sediment in the fuel tank. Drain off a sample from the bottom of the tank

- Check a raw water strainer and clear it if necessary

- Check battery electrolyte levels. Top up if low

Annually:

- Check cooling system anodes, replacing them as necessary

- Closely inspect all hoses for cracking or other signs of deterioration. Check all hose clips for tightness

- Check the air filter, wash or replace it as appropriate

- Check the exhaust elbow for corrosion. Ideally, you should detach the exhaust, so you can have a look inside

- Check engine mounts for deterioration. Look for loose fastenings and separation between rubber and metal components

- Check the shaft coupling and make sure all bolts are properly tightened

- Replace oil and oil filters every 100 to 150 operational hours or at the end of each season, whichever comes first

- Change gearbox oil every 150 hours or annually, whichever comes first

- Replace fuel filters every 300 hours

- Replace saildrive diaphragms after seven years

Winterising:

- Change the engine and gearbox lubrication oil, replacing any filters

- Darin the freshwater cooling system and refill it with a fresh solution of antifreeze

- Flush the raw water system through with fresh water if possible

- Check the raw water filter. Clean if necessary

- Remove the pump impeller. Pop it into a plastic bag and tie it to the keys, so you won’t forget to refit it

- Drain any water or sediment from the fuel tank and fill the tank if possible

- Also drain any contaminants from the pre-filter. Replace the filter elements

- If possible, squirt a little oil into the air intake and turn over the engine (don’t start it!) to distribute it over the cylinder walls. Some manufacturers recommend removing the injectors and introducing the oil that way – refitting the injectors once you have done so

- Change the air filter and stuff an oily rag into the intake. Do the same to the exhaust. Then hand a notice on the engine to remind you they are there!

- Relax and remove all belts

- Rinse out the anti-siphon valve with fresh water. Reassemble it if you’ve taken it apart

- Check the engine over thoroughly: engine mounts, hoses and their clamps (need to be tightened from time to time), exhaust and the exhaust elbow, and the electrical wiring

- Remove the batteries and charge them fully

Diagnostics and troubleshooting

Engine cannot crank at all:

- Low motor battery voltageSwitch to domestic batteries if they still hold the powerOlder engines can be started by opening the decompression level and cranking by handAnother trick employed by Vendee Globe champion Micheal Desjoyeaux is to wrap a line around the engine pulley at one end with the other end connected to the end of the boom. A quick gybe might have enough power to crank the engine

- Loose or corroded connections

- Battery switch is off, or defective

- Circuit breaker is tripped

- Solenoid or starter motors are defective

- Faulty key type switch

Engine surges or dies:

- Out of fuel. Either bad planning or fuel gauges are faulty

- Fuel cock shut – perhaps partially

- Blocked or partially blocked filters

- Fuel line blocked. Suspect the diesel bug!

- Water in the fuel

- Fuel lift pump defective – perhaps a split diaphragm

- Air in the fuel. Suspect a loose connection or leaking seal somewhereLearn how to bleed the fuel system if air gets into it

- Tank air vent crushed or blocked. There’s a partial vacuum in the tank

- Split fuel line

- Fouled prop

Shake, rattle and vibration of the engine:

- Bent prop shaft

- Damaged or fouled propeller. Prime suspects if the prop has recently been seriously fouled by flotsam. Possibly a lost blade, particularly likely with folding and feathering props

- Broken engine mount

- Loose shaft coupling

- Loose shaft anode

- Cutless bearing failure

- Gearbox failure. If so, you should be able to hear it if you can get close enough

- Internal engine failures, such as big end bearings, main bearings or valves. This should be clearly audible

Smoke signals – black or grey:

- Too much load on the engine. If black smoke emerges when moving from a standstill but clears very quickly, you may simply open the throttle too much.

- A dirty, weed hull will cause lots of extra drag. So will be towing another boat

- Thermostat is stuck closed, and the engine cannot cool down. As an emergency, you could remove it completely or better remove the valve’s moving parts (thermostat’s innards) and reassemble the housing (empty carcase)

- Too large or over-pitched prop. The engine is simply struggling to turn it

- A fouled prop. If the boat speed suddenly slows this is a very likely cause

- Dirty air filters. The engine isn’t breathing deeply enough

- Engine space ventilation has been reduced. Look for items that might be blocking the air’s path forward the engine

- Turbo failure – not enough air is getting into the cylinders

- Constriction of the exhaust system causing high back pressure. Perhaps a collapsed exhaust hose or a partially closed seacock

- Faulty injectors or injection pump

Smoke signals – blue:

- Thermostat is stuck open, and the engine is running too cool. The engine is running below its normal operating temperature. You have to replace the thermostat

- Worn valve guides

- Worn or seized piston rings

- Turbo oil seal failure. Lubricating oil is escaping into the hot exhaust gases

- Crankcase has been overfilled

- High crankcase pressure due to blocked breather

Smoke signals – white (should not persist for more than a few seconds, normal when the engine starts due to water vapour):

- Water in the fuel – most probable if the engine runs erratically

- Cracked cylinder head casting

- Blown head gasket. Cooling water is escaping from the galleries and entering a combustion chamber

- Cracked exhaust manifold

Overheating alarm sounds:

- Reduce the revs and check the exhaust outlet for raw water flow and stop the engine

If there is no or little water spurting from the exhaust it could be:

- Seacock partially or completely shutClose the seacockCheck that no objects (e.g. plastic bag) are obstructing the seacockRe-open the seacock

- Blocked, or partially blocked, raw water inlet or strainer

- Plastic bag over sail drive leg or seacock

- Air leaks in the strainer seal – the suction is being lost

- Damaged water pump impeller. Check the rubber impeller is slightly flexible, not hard, and replace it if necessary

- Split hose somewhere

But if there’s a good flow of water from the exhaust it could be:

- Thermostat failed in the closed position

- Loss of freshwater coolant. This could be a hose, the heat exchanger or even a calorifier

- Slack or broken drive belt. If the belt also drives the alternator, you would also expect the batter light or alarm to be activated

- Oil warning light or an alarm activated

- Shut the engine down immediately

- Check for engine oil leaks, crankcase oil level, pressure relief valve, defective sender unit or wiring

Alternator charge alarm sound:

- Stop the engine and investigate

- Broken or slack drive belt. If it’s also driving the raw water pump, the engine will rapidly overheat and the exhaust system could be seriously damaged by uncooled gases

- Defective alternator

- Power to alternator field coils interrupted

- Wiring fault or short circuit

- Glow plug remaining on (if fitted)

General lack of performance:

- Marine growths on hull or prop

- Damaged prop – possibly a bent blade

- Turbo failure or accumulated dirt

- Blockage to the fuel system. Check the pre-filter first to make sure it’s clear

- Cable not opening the throttle fully. It could be broken or frayed, or the holding clamp could have vibrated loose

- On stern drives and sail drives the propeller bush could be slipping

- Lack of engine pressure in the cylinders – the engine is in need of an overhaul

If you cannot repair the engine

- Sail to a marina where you can repair the engine or get it repaired.

- In the right conditions and place, you could berth using sails alone, otherwise, send Pan Pan alert with VHF on channel 16 to get assistance.

Rig failure

Prevention:

Almost everything on board a yacht relies on the rig, and yet, often, it is not given the attention it deserves. Most rigging failures can be prevented by a careful inspection before passage and replacing rigging after five years or so of hard offshore use. The rigging is often neglected because of time pressure and lack of technical knowledge. The most common rig failure has been documented by Pantaenius.

- Inspect rig periodically (also underway) for damage and defects: yacht inspection checklist. It also makes sense to have a rig check carried out by a trusted rigger on a regular basis. Their trained eyes can detect potential faults or areas that could fail at an early stage

- Tune rig properly: step-by-step guide, sail and rig tuning book

- Plan passages to avoid bad weather and hurricane season. With modern forecasting, a true storm will rarely arrive unannounced, but as you venture further offshore the chances of being caught out increase.

- Avoid accidental/Chinese gybes as they damage the rig and bring it down. Tie a preventer line from the boom end (mid-boom is not as good) to a block at the bow or around a cleat and then back to a winch in the cockpit to tighten the preventer properly. Alternatively, use a boom break to slow the boom to a crawl. Make sure the kicking strap or boom vang is tight so the boom cannot lift and create slack for the boom to violently swing around.

Steps:

When a piece of standing rigging breaks, the first priority is to take the strain off the affected portion of the rig. But don’t reduce sails immediately, as the sails and halyards may be holding something up. Once the load is moved to the opposite side and reinforced, you can reduce sails. If a stay, shroud or spreader fails, but your mast is still standing, you may be able to use a halyard, topping lift or spare line to support your rig. This may buy you a little time while you secure the line and transfer the load. Useful backup is a roll of stainless-steel rig wire rope (or HMPE line), slightly longer than your longest stay and a compression terminal, such as Sta-lock that can be used to quickly fix a wire.

You may need to have tools and spare parts on board to fix rig failures. At a minimum, you should have tools to cut your rig loose and make minor repairs. The attached rigging spares checklist from Rigworks contains a comprehensive list of items that you might want to have on board. Before heading to sea, think through any other methods you could use to detach stays and shrouds other than cutting, for example removing pins, unscrewing bottle screws, removing a furler from the deck etc.

Protect the crew as much as possible. If the mast is going to come down there is less risk in having one person on deck than a full crew.

Dismasting (losing the mast)

- Ensure that the crew is safe. Put on a life jacket and harness.

- Designated person sends Pan Pan alert with VHF on channel 16. In case you lose your VHF aerial and radio communications, use a portable VHF or satellite phone.

- Check the boat for structural damage to ensure that you are not taking water. But don’t start the engine until the mast and any other wreckage are cleared to avoid fouling the prop.

- Get your liferaft and grab bags ready to deploy.

- Decide whether the mast can be safely secured to the boat or needs to be cut loose. If you are in rough conditions, and the mast is likely to sink the boat, don’t hesitate. Cut it loose (hacksaw with bi-metal blades – effective and cheap, hydraulic cutter or battery-powered angle grinder – effective but expensive).

- If you can safely save the mast, get a heavy-duty gloves and secure the mast tightly to the deck. Pad any contact points using fenders or bunk mattresses to minimize further damage to the boat.

- After clearing all lines from over the side, start the engine and motor to a port if you are within the motoring range. However, if you are outside the motoring range, you will have to set up a jury-rig with the remains of the broken mast or other spars like the boom or spinnaker pole. Keep a roll of 1x19 stainless-steel rig wire rope, slightly longer than your longest stay, for emergency stay/shroud construction. A 6mm HMPE line is a good alternative with even higher breaking strength.

Forestay failure

- Unless you have a strong inner forestay, you probably don’t have much time here. Warn your crew that the mast will probably come down

- Alter course downwind to reduce the load on the forestay

- Support the rig by setting up a jury forestay with a spinnaker halyard or spare line somewhere around the anchor fittings. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

- If the forestay failed at the base, you can try to reconnect

Backstay failure

- Head upwind immediately to reduce the load on the backstay

- If you have running backstays, tighten them up and reef the main sail below the point where the running backstays connect to the mast (the main sail will provide some support for the mast)

- Support the rig by setting up a jury backstay with a main halyard, topping lift or spare line. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

Shrouds or spreaders failure

- Quickly tack the boat and ease the load on your sails so that the failed components are on the leeward side and the load is reduced

- Support the rig by setting up a jury shroud with a halyard or spare line to the chain plate or turnbuckle. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

Rig cutting options

- Hacksaws and multiple spare blades – highly effective on rod rigging

- High-quality bolt croppers – effective on Dyform, but not effective on rods

- Hydraulic bolt croppers – effective on Dyform and rods

- High-quality angle grinder – potentially useful for cutting rods and Dyform

- Sharp, deck–mounted safety knives

- High-quality scissors

Broken or lost halyard

- Make sure to always leave the topping lift loosely attached or have a boom strut that can support its weight. The mainsail is what holds the boom up under sail, so if the main halyard comes loose you have a potentially dangerous situation in the cockpit

- Get the boat hove to reduce the motion and minimise speed

- Take the sail down

- Go to the top of the mast to assess the situation – best done alongside in calm conditions

- If the line has not gone down into the mast, grab hold of it and bring it down. If it is still long enough, remake the halyard. If it is too short, reeve a new halyard to the end of it and keep pulling through

- If the line disappeared down the mast you have to get the reset the halyard. Lower a weighted thin messenger line down from the top of the mast until it is just past the exit gate for the halyard near the deck. The weight generally makes enough noise against the mast to hear where it’s currently at. Fish the messenger line out with a thin mousing wire shared into a hook to grab the line. Now pull the messenger line out of the gate and down to deck level. Now attach a new halyard to the messenger line and pull it through

Sail jammed on a furler

Sail jammed opened:

- Have a quick check with the binoculars that it is not a halyard wrap. If it’s not, the most likely scenario is that the sail opened too fast, or with not enough sheet tension, and the furling line is now jammed in the drum

- If it is safe to do so, open the drum and manually unwind the line, before re winding it. If this doesn’t help, there is likely a problem with bearings in the swivel or drum

- Lower the sail traditionally: unattach the tack from the furling drum and lower the sail with a halyard, pulling it out of the foil

- Inspect and repair it, if it is safe to do so

Sail jammed half open:

- Check to see the furling line is not jammed in the furling unit

- If the control line is too thick or too much is left on the furling drum, it’s possible for a jam to occur. Ideally, look to have three turns left on the drum when fully stored

- If the control line is not jammed, there are likely other issues such as seized swivel drum unit bearings or a halyard wrap. Wait for the wind to drop, remove the sheets, manually unwind the sail, drop it and find the cause of the issue

Sail jammed in between (not completely furled):

- Motor in circles to wrap the sail around the forestay and passing the sheets around the sail. If needed remove the sheets but be super careful. Lash with sail ties or rope where possible

- Alternatively, use a spare halyard to wrap around the sail

- If nothing works and the situation is getting out of control, cut the sail off

Halyard wrap around the forestay:

- Try opening up the sail again, depower it and let it luff a little to shake things loose. Then try refurling. You may need to do this multiple times to get the sail fully furled

- Lower the sail traditionally: unattach the tack from the furling drum and lower the sail with a halyard, pulling it out of the foil

- Find out the root cause and fix. Usually, it’s because the remaining halyard is too long or its lead angle to the swivel is too vertical (lead to the swivel should be at around 10-15°). A loose forestay can also cause wraps, so check tension. Make sure the furling control line heads into the drum at 90° to prevent riding turns (jam of the line)

In any case avoid using winch to furl the sail away! If the swivel is jammed, the furling line has riding turns or the bearings are gone, putting more force on the system will likely increase the problems.

Steering failure

Steering tends to be one of those things taken for granted until it no longer works. Many boats are abandoned each season due to failed steering systems because the skippers cannot make them head in the direction they need to go. Planning for steering problems involves two main pursuits. The first is inspecting and maintaining the steering system, and the second is planning for what to do should that system fail while underway.

You should regularly perform proper maintenance and inspections of a steering system before heading out to sea. Proper maintenance means mechanical inspection, tension tests and lubrication. Anyone with basic mechanical skills can do the maintenance, both quickly and relatively inexpensively:

- Comprehensive steering system inspection checklist

- Basic steering system inspection checlist (see “Inspect steering system” section).

Make sure you carry spares for your system as well. Having a few simple spare parts can make a big difference should a failure occur. For mechanical systems, make sure you have spares for items likely to wear and break such as the chain and cable. A few spare pulleys and clamps could be helpful as well. For hydraulic systems, make sure there is a good supply of fluid of the right type and a few spare hydraulic fittings

Steps:

- Slow down.

- Assess the extent of the damage and see if the hull integrity has been compromised.

- Engage alternate or emergency steering (see below).

- Try to centre the rudder (easier to limp home with an engine or sails or be towed).

- Predict if you need help, e.g. towage.

- Consider anchoring if water depth and conditions are appropriate.

- SAFETY or URGENCY message broadcast, if appropriate.

- Active Not Under Command (NUC) lights, shapes and sound signals, as appropriate.

- Apply remediation actions (see below).

Loss of control of the rudder

This may be due to a breakage in the steering linkage or the rudder breaking loose from the shaft and just spinning on the shaft.

- Engage autopilot. Autopilots ram is attached to the rudder post with its own tiller arm, so you can use autopilot for emergency steering.

- Prepare emergency tiller in case of issues with the autopilot.

- Use hydraulic pumps to steer the rudder if possible.

Loss of the rudder

It is usually the result of the rudder shaft breaking and the rudder simply falling away. It is best to give this some thought while at the dock, put together a kit of parts to use when needed, and practice to make sure it works for you.

Methods:

- Set up a jury rudder (difficult but has been successfully used by many sailors). Most boats do not carry such a piece of gear aboard, so something will have to be fabricated and deployed while at sea. Use materials that may already be aboard that can be used to put together an emergency rudder (e.g. spinnaker or whisker pole, rudder head, plywood panels like small cabinet doors, or gangway). The emergency rudder should be about half the size of the original rudder to make it easier to deploy and use.

- Tow a drogue (e.g. Seabreak drogue) to pull on one side of the boat or the other in order to steer (has been successfully used by many sailors). If you do not have a drogue, even a stout bucket should work. Depending on the size of the drogue this may slow the boat down considerably and be inefficient if you have to go against wind and high waves

- Trim the sails to balance the boat (might only work on a limited range of headings and generally does not work well for most sailboats)

This Yachting Monthly article explores this topic in great detail.

This video is also worth watching to understand how to set up a drogue for emergency steering.

Jammed rudder

Probably the most difficult to deal with is the rudder becoming jammed and stuck in one position.

- Verify that the problem is not in the linkage or drive system: check that the autopilot is not holding the rudder over and gears in the lockers are not blocking moving parts of the steering. All it takes is a fender or dock line to jam a steering system

If it is clear that nothing inside the boat is blocking the travel, it will be that the rudder itself is stuck. It could be that the rudder jams against the hull or a result of something like a crab pot stuck in the rudder.

- Try to break the rudder loose by using the emergency tiller

- Dive to clear the rudder (only in calm see!)

Restricted / Poor visibility (fog, heavy rain, snow, …)

- Do not leave your berth, maybe unless you know there are only occasional patches forecasted.

If you get caught out on the sea:

- Log a position and plot the fix on the chart when you see a sign of fog development.

- Put on lifejackets (the decision whether to clip on is the skipper’s. You must take into account traffic density and the sea state).

- Post a dedicated look-out at all times.

- Gather the fog horn, hand bearing compass and flare pack.

- Have the engine ready for immediate use (keep in mind the manoeuvrability vs noise trade-off).

- Raise your radar reflector if not permanently fitted.

- Turn on your navigation lights to increase your visibility.

- If you are motoring, keep the mainsail hoisted to increase your visibility. Avoid any complicated setup for the time being: spinnakers, cruising chutes, preventers and poling out headsails.

- Disengage autopilot and check rudder response to hand steering.

- Have a liferaft, EPIRB or PLB ready to deploy.

- Slow down and proceed at a safe speed (3-5 knots). Sailing too slowly can prolong the misery and makes any alterations of course less obvious on another vessel’s radar.

- Keep a sharp look-out, using both sight and hearing (Rule 5 of ColRegs), and assign extra pair of eyes if possible.

- Tune VHF to the relevant channel(s): Ch 16 when offshore as well as the local harbour or VTS channels when appropriate.

- Use an echosounder, radar, GPS and AIS to build a picture of what is around. Radar is essntial in restricted visibility. If a fog signal is heard it may be difficult to accurately determine the direction of the fog signal. Without radar in restricted visibility you are pretty much blind in the water. Stay clear of any traffic and don’t risk pilotage into tricky and busy harbours.

- Know from which direction the predominant traffic is likely to approach from and if possible, keep clear of busy areas. If necessary, turn parallel to the traffic flow until it calms down.

- Sound required signals in restricted visibility as per Rule 35 of ColRegs with a fog horn or whistle (large ships only have a range of 2 miles, range of your signal will be even less!):If you only use sails: sound at intervals of not more than 2 minutes one prolonged blast followed by two short blastsIf you use the engine, and you make your way through the water: sound at intervals of not more than 2 minutes one prolonged blastIf you use the engine, but you are not making your way through the water: sound at intervals of no more than 2 minutes two prolonged blasts in succession with an interval of about 2 seconds between them

- Get the yacht into an area where the risk of collision is reduced, e.g. leave the shipping lane, find a bay to anchor to sit it out. Making landfall in fog is generally not advised due to the navigational dangers and the fact that the harbour may still be active with commercial vessels.

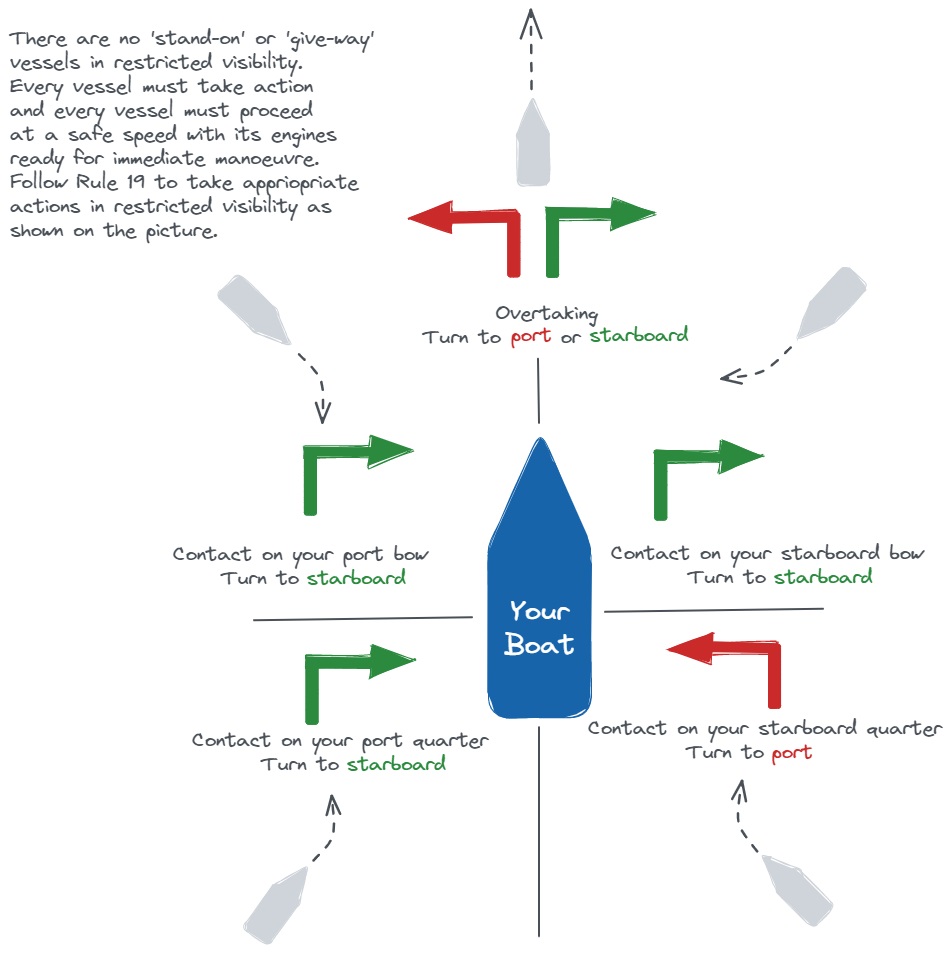

- Use Rule 19 to avoid collision when close-quarters situation is developing. Note that there are no stand-on vessels in restricted visibility. All participants are required to take appropriate avoiding action.

If you hear the fog signal of another vessel forward of your beam, or if you are unable to avoid a close-quarters situation, reduce your speed to the minimum required to maintain steerage. If necessary, stop your vessel entirely. In any case, navigate with extreme caution until the risk of collision has passed. Keep in mind that course alterations are generally more noticeable to other vessels than speed changes, so prioritize altering your course if it is a viable option.

Sails rip

Prevention

- Don’t let the sails and leech flog/flutter in the wind. If left too long, it can shred a whole sail in a matter of minutes. Flogging in the wind for half an hour may shorten the sail’s lifespan by months. Use leech line to trim tension of the leech to avoid flutter and adjust cars to keep pressure in the leech at the top of sail.

- Avoid chafe (e.g. pad spreaders and spreader ends with foam insulation when on longer crossings and tape patches of sail tape on the sail where it chafes against the spreaders, ensure there are no sharp pins on the turnbuckles).

- Reef according to wind/gust conditions (seams, clew rings, reef cringles and webbing put a lot of stress on the sailcloth and are most prone to rip in a squall).

- As soon as you have finished sailing, cover your sails to protect it from degradation caused by UV rays. Take off the sails after the season and do not leave them up when the boat is stored, whether in or out of the water.

- Reinforce any loose stitching immediately (“a stitch in time saves nine”).

Repair

- When a seam breaks, it could be temporarily solved by taking in a reef above the split if possible.

- If it is a roller furling sail, you should take it down rather than just furl it away, as furling a shredded sail can make it very difficult to unfurl again.

- Get the sail down (small tear may soon become a much bigger one).

- If too far from a sailmaker, make temporary repairs to the sail.

- Repairs to high load areas may require both patching and sewing:Remove old remnants of thread with scissors, flatten, clean with alcohol, align sides in tear, by putting smaller pieces of tape to line up the rip.Put a bigger patch and fold to reinforce the other side of the sail.Always round patches and start some centimetres outside the tear. Flatten the tape as you peel back off the backing, making sure no air bubbles form under the tape. After the patch has been attached, use the back side of a spoon (or similar) to press crinkles and air out. Even better, use a hot air gun, a hair dryer, the underside of hot kettle or similar, to make the glue bond properly.Large repairs can be done with non-sticky sailcloth can be glued with 3M, Sikaflex or similar.If necessary, use double-sided tape to keep panels together and reinforce with stiches. Put protective sticky-back tape over the new stitching.

Heavy weather / Bad weather / Adverse Weather

Preparation:

- Verify your position

- Make a plan and consider re-routing: assess your situation (shipping lanes, lee shore and shallows) and make a plan, e.g. escape to port of refuge, steer downwind, going into deep water from anchorage / port

- Update weather forecast and plot storm position and possible track

- Adjust watch rota if needed to ensure adequate coverage, put away non-essential tasks

- Brief the crew: expected conditions, take seasickness tablets, prepare clothing, restrict access to decks. Inform but do not frighten, keep crew morale up

- Cook and eat a decent meal: make sure that everyone is well rested, fed and watered and that some food is prepared before the bad weather hits (e.g. sandwiches, hot water in a thermos)

- Reduce windage and clear loose gear on and below deck: remove bimini, deflate dinghy, close lockers etc.

- Increase stability (GM), e.g. fill ballast tanks if fitted (move centre of gravity down towards added weight), move spare anchor below deck

- Make the boat watertight: close all deadlights / hatches, ports and washboards, cover air vents, hawse and spurling pipes, rig stormboards / cover large ports with storm shutters or plastic coverings from outside, close all sea valves / through-hull fittings that are not essential

- Clear scupper and freeing ports (water freeing arrangements)

- Reduce free surface to minimum (completely fill or empty tanks)

- Check all bilge pumps and pump the bilge dry

- Boat check-up: engine, batteries, steering gear, all safety gear including liferaft, deck lights, emergency communication, fittings and anchor attachment, hawse and spurling pipe covers fitted and sealed

- Rig lifelines / jackstays, put extra lashing as necessary (e.g. tack/cunningham and cringle)

- Prepare headtorches and searchlight, and wear life jacket and safety harness if necessary to go on deck

- Reef sails: reduce sails early and hoist storm sails whilst you still can, and certainly before dark. The force on a sail varies directly with air density and the square of the wind speed. Cold air is denser than warm air and so creates a greater force (could be up to 30% or so). Wind force does not increase in direct proportion to the wind speed, but rather in proportion to the square of the wind speed. A 40kt wind has 4 times the force of a 20kt wind (4040 is 4 times larger than 2020)

- Prepare a sea anchor or a drogue if that is your storm tactic before the weather is too bad

- Turn-on Radar as visibility is likely to be bad. Prefer S-band as it works better in rain

- Engage autopilot and stay inside if possible, engage manual steering only if autopilot cannot cope

- Update your location to all vessels in immediate area as appropriate

- Be ready to alter course and speed to reduce rolling and avoid broaching

Storm techniques:

1. Head for safe harbour / anchorage if you can reach it before the bad weather hits or head far off predicted track

2. Avoid breaking waves if you can and keep the bow or stern oriented towards the seas

3. Steer downwind course (run before) if you have enough sea room, a competent helmsman or very good autopilot. This active storm tactic is suitable for modern lightweight boats with flat bottoms and wide beams.

4. Beat possibly with the assistance of the engine. Probably not sustainable in the long run because of fuel limitations and the stress on the engine itself from operating at extreme angles of the heel. But a viable option in coastal conditions and when you have to escape the lee shore

5. Heave-to if your boat can. This passive storm tactic can be suitable for traditional voyagers with long/full keel:

6. Forereach if you don’t have enough sea room and the sea is not breaking. This active storm tactic works by keeping the boat moving forward to windward (45-60 degrees to the wind) at low speed:

7. Lay ahull (only as a last resort):

6. Drop an anchor if you are blown into the lee shore and don’t have sea room

Storm techniques and preparation are described in great detail in this article.

Reporting requirement

If you meet any sever weather conditions (e.g. tropical revolving storm, sub-freezing air temperature) or any navigational danger (dangerous ice or derelict not under control) that was not forecasted or announced, you have the responsibility to report this to shore facilities and other vessels in the vicinity (Safety Message).

Preparing the boat for a hurricane in the harbour:

- If possible, haul the boat. Put her as far away from the water and above the ground as possible to avoid the destructive effects of storm surge

- Otherwise, leave the boat at a well-protected floating pier that will rise with the surge

- Reduce windage: remove sails, sprayhood, bimini, sheets, snatch blocks, ventilators, lifesling, dinghy, deflate dinghy and stow it below or onshore etc.

- Close all through-hull fittings

- Set out as many fenders as you can find. To keep them in place, tie plastic bottles full of water (5L) to the bottom of each fender

- Double-up mooring and docking lines and their chafe protection. Leave a spare line in the cockpit so a Good Samaritan can help

- Get off the boat. There is little or nothing you can do on board at the height of a storm except endanger your life

Hit by sudden gust/squall

Gusts are generally short lived, but because the wind speed can temporarily double in speed over a very local area they can pose a significant challenge to yachts.

Prevention:

- Monitor weather for any signs of squall / gust development (e.g. appearance of cumulonimbus on the sky, lightning, detection by radar), occluded fronts are particularly prone to gusty conditions

- Observe other sailing vessels to windward

- Research the local area: some areas are particularly prone to gusts caused by local orography

- Have your lines prepared for immediate manoeuvre, don’t lock main sheet

- Reef the sails according to the expected gusts not the regular wind. This is especially important for multihulls as they lose stability at a relatively small angle of heel. Therefore, all multihulls are capable of being capsized by wind action alone if too much sail is carried

- Reduce sails before the squall hits

- Maintain reduced sail area in restricted waters as you won’t have much sea room to manoeuvre

Steps:

- Easy the traveller all the way to leeward side

- Easy the main sheet and or vang to depower the mainsail

- If close reaching head up

- If beam reaching or broad reaching, bear away

- Start the engine and power into the squall to ease the strain on the sails

- Reef or even drop the sails

It may be enough to just use one method, or it may be necessary to use all of them depending on conditions.

Knockdown

Knockdown is a situation where a is knocked over to its side, causing the mast to nearly parallel or even touch the water. This event is a form of capsizing, albeit less severe.

- Check to see that everyone is still aboard and unharmed

- Pull up floorboards to determine if you are taking water

- Get all available bilge pumps working as there is likely to be a lot of water inside the boat

- Reef the sails

- Once the situation is stabilized inspect the rest of the boat as rigging damage is common in knockdowns

Lightning

Lightning is the thing that scares most of us at sea. The only really preventative measure to avoid lightning is to sail in the opposite direction and hope for the best. Lightning can strike up to ten miles away from the cloud that generated it. Just because you are in the midst of a thunderstorm doesn’t mean you will get hit – there are many sailors who reported lightning striking the water next to their boat but not touching them. Others that were struck reported varying damage to electrical equipment and none experienced structural damage or fire.

The boat should ideally provide a direct route “to ground” down which the lightning may conduct to minimize damage. Most modern boats have the mast bonded to the keel by manufacturers. The masthead unit will definitely be destroyed when lightning hits a mast but with a lightning protection system the remaining electronics may survive. A high-tech solution is the Sertec CMCE system, which claims to reduce the probability of a lightning strike by 99% within the protected area. The system has been widely installed in airports, stadiums, hospitals and similar, but has now been adapted for small marine use.

Weather forecasts are still not particularly good at predicting thunderstorms with increased potential for lightning. In particular, they are not very reliable in terms of predicting the exact area.

Preparation

- Sound travel at a speed of 5 seconds a nautical mile. So when you see a lightning flash, start counting and divide the seconds by 5 to get the distance to the lightning (5 seconds = 1 mile, 15 seconds = 3 miles etc.). Thunderclaps can be heard for around 25 miles, so if the sky on the other side of the horizon is alive with light, but you cannot hear claps then the storm is still a way off. Keep moving but be vigilant

- Keep a 360° visual and radar look-out: due to the immense height of thunderclouds they are pushed along by the upper atmosphere wind, not the sea-level breeze. This makes it difficult to predict which way a cloud is moving. They can sneak up behind you while you are sailing upwind

- Reef to prepare for a squall: wind associated with thunderclouds can reach in excess of 40-90 knots in a matter of seconds, this will often be combined with torrential rain and drastically reduced visibility. The strong winds of a squall come with the rain. If the squall approaches without rain, the worst is yet to come. If it approaches already raining, the worst is past

- Unplug all masthead units, including wind instruments and VHF antennas and ensure ends of leads are kept apart to avoid arcing

- Put handheld or portable electronics (VHF, mobile phone, EPIRB, PLB, sat-com etc.) temporarily inside a metal oven. There is a theory that the oven on a yacht can act as a Faraday cage, protecting anything inside it from the effects of electrostatic discharge (ESD)

- As the storm gets turn off all electronics and use traditional dead reckoning navigation. The modern kit has increasingly efficient internal protection, but manufacturers still advise turning it off

- Turn on the engine. In case your batteries are fried, and you can’t use your sails you will be able to keep full control over your vessel

- Stay down below as much as possible

- Avoid touching metal around the boat, such as shrouds and guardrails. Areas such as the base of the mast, below the steering pedestal and near the engine have the highest risk of injury

Take into consideration that you should take protective measures also in the harbour and at anchor. If lightning strikes a utility pole the current travels down the electricity cable looking for ground. It can enter a vessel through the shore power line or can pass through the water and flash over to a yacht at anchor.

After the boat is struck

Expect masthead units, VHF antennas and lights to be destroyed, so make sure you carry a good quality spare VHF antenna.

- A nearby strike will be blindingly bright. Sit in the cockpit until your night vision returns

- If you or a crew member is hit, they could suffer from cardiac arrest - if so, reanimate immediately

- Check for any fires and put them out ASAP

- Make sure the bilge is dry and there are no holes in the hull

- If you have engine power, try to motor to safer waters

- Inspect the boat, e.g. main mast wiring, navigation lights, electronics, autopilot etc.

- Fluxgate compasses can lose calibration following a strike. Check all electronic compass readings with a handheld compass

- Call for help if needed and head to the nearest harbour. Until the boat had been lifted, inspected and checked below the waterline, you could not consider it seaworthy

Injury and getting medical advice

The severity of sailing injuries can range from small cuts or scrapes to violent blows to the head or a crew overboard in frigid waters. Serious physical injuries involving broken bones or bleeding may need outside assistance. Once first aid is applied, the casualty should be made comfortable and Pan Pan Medico call made. This may result in the evacuation of the casualty by rescue services.

Try to anticipate situations before they become emergencies. Many situations can often be prevented. Get the boat under control, prevent any additional injuries or boat damage and try to reduce further risks.

Taking a First Aid/Medical care course is a good investment of money and time especially if you plan ocean passages:

- RYA First Aid (1 day)

- MCA STCW Medical First Aid (4 days)

- MCA STCW Proficiency In Medical Care On Board Ship (5 days)

Steps:

- Stay calm but act swiftly. If you get hurt you will not be able to help others.

- Apply first aid and consult Ship Captain’s Medical Guide as required. Follow the DRSABCD action plan: Daner, Response, Send, Airway, Breathing, CPR, Defibrillator.

- Give immediate treatment to the casualty who is not breathing and/or whose heart has stopped, is unconscious or bleeding severely, others can be treated later.

- Record body norms:Temperature: 36.9 degrees C - normal, < 35 degrees C - hypothermia, > 41 degrees C - dangerous fewer.Pulse rate: normal restring rate for adults 65-80, unless very healthy then less.Respiration rate: normal rate is 16-18 breaths per min for adult male – can count by looking at the chest.

- After brain injury measure a person’s level of consciousness by using Glasgow Coma Scale. Sum scores for Eye, Verbal and Motor tests. Anything below 15 means there is a problem.

- If you are subscribed to a telemedicine services get in contact with them, e.g. praxes

- Make Pan-Pan or Mayday (imminent danger) radio call on MF or VHF to get in contact with nearest RCC.

- If you are Offshore, get in contact with the nearest RCC via satellite system (e.g. voice call or special access codes using Inmarsat system: SAC 32 for medical advice, SAC 38 for evacuation, SAC 39 for maritime assistance). GMDSS compliant satellite voice communications systems, or mobile phones, can be used for medical advice or assistance, but should not be relied upon as the only means of communication.

- Getting causality ashore as quickly as possible, by medical evacuation if necessary.

RCCs are able to communicate with vessels 24 hours a day, 365 days a year to coordinate medical advice and assistance, sometimes through a Telemedical Assistance Service (TMAS) as well as coordinate medical evacuations from vessels at sea.

TMAS is a medical service permanently staffed in many countries by doctors qualified in conducting remote consultations and well versed in the particular nature of treatment on board ship. TMAS telemedical advice is available free of charge. You can contact Telemedical Assistance Services (TMAS) through the RCCs. They will collect basic details including the casualty’s illness or injury, type of vessel, next port of call or nearest port at which the casualty could be landed, and confirmation of the vessel’s current position. The call will likely then be transferred to one of the TMAS providers. Once the RCC connects with the TMAS doctor, they will directly connect you with them.

Contact details (examples):

- UK MRCC: +44 (0) 344 382 0028, [email protected]

- UK Coastguard who will also contact one of the UK’s designated TMAS provider: +44 344 3820026 and +44 208 3127386

- C.I.R.M Italian telemedicine assistance for ships flying any flag (free, round-the-clock): +39 06 59290263, +39 348 3984229 (mobile), [email protected]

Helicopter / SAR evacuation

Medical evacuation by helicopter is undertaken very rarely as it involves risk to the casualty and crew of the vessel and helicopter. The normal limit of helicopter rescue is within 200 nm of operational base. The helicopter rescue crew instructs on how to rescue the yacht’s crew or casualty and will try to communicate directly using marine VHF radio. SatCom and HF may be used at long range.

Requesting helicopter / SAR assistance

- Contact RCC, give vessel details, name, call sign and contact numbers, vessel position, speed and course, local weather conditions.

- Give as much medical information as possible, particularly about the patient’s mobility.

- Indicate landing or winching area.

Preparing patient before arrival of helicopter / SAR boat

- Move the patient, in accordance with medical advice, as close to the helicopter pick-up area as the patient’s condition permits.

- Update the information on medication given.

- The casualty should be dressed, wearing lifejacket and ready (with medical records, mobile phone, passport, other personal documents, money, credit card attached, no luggage). Use MCA Medical Form MSF 4155 to make the detailed medical report (keep a few copies on board). The purpose of the report is to inform the doctors on shore exactly what happened to the casualty, what treatment they have received and how they have progressed.

Vessel preparation

- Everyone to put on life jackets and harness.

- Update position to RCC and / or helicopter / SAR boat including course and speed to the rendezvous position.

- Agree on frequency communication with helicopter. Depending on the country the communication might also be done via mobile phone.

- Clear the deck of loose objects below before the helicopter arrives. Clear the port quarter of obstructions.

- Do whatever you can to attract attention and signal your position: red hand-held flares (night or in bad visibility), orange smoke (daylight). If you do not have these, wave ensign or hi-vis life jacket. But do not fire parachute flares when the helicopter is closed by!

- Fly flag (illuminated at night) to indicate wind direction to the helicopter pilot.

- Switch off radars during pick-up / landing.

- Take wind 30 degrees on port bow. The reason for port tack is that the primary pilot and winch man sit on the starboard side so they can see the vessel better.

- If your engine is powerful and reliable, or if there’s very little wind, drop the mainsail and headsail. If you don’t trust your engine or are in any doubt about it, get ready to sail close-hauled on the port tack with the main sail up.

- Steer steady and straight course in the direction the helicopter crew asks.

- Have a portable radio ready for communication from deck to helicopter.

- At night, direct available lighting to illuminate the pick-up area. Do not direct lights towards the helicopter as it will adversely affect the pilot’s vision.

- Wear rubber gloves to handle winch wire to minimise electrical shocks / rope burns.

- Brief the crew – it will be too noisy when the helicopter has arrived overhead. During the recovery do as the helicopter crew tell you – they are the experts.

Patient recovery

- When the helicopter is in position, a winch person (usually preferred method) or a weighted line be lowered (hi-line method). Allow the line to touch the boat or the water first to discharge any static electricity. Then take up the slack and stow the loose end in a bucket to avoid snagging.

- Do not touch the winchman, stretcher or winch hook, or lead which hangs down from the winch person until it has been earthed. Use gloves and coil hi-line into the bucket.

- Do not tie the line to the boat and do not let it get snagged, particularly on any crew.

- Do not transmit on radio whilst winching is in progress.

- When the helicopter is in position, a weighted line will be lowered first (hi-line method). Allow it to touch the boat or the water to discharge any static electricity then take up the slack and stow the loose end in a bucket to avoid snagging. Use gloves and do not tie the line to the boat!

- If a helicopter crewman is lowered, follow his instructions. As the winchman is lowered on the wire, keep some tension on the line but only pull it in when told to do so - this may require the efforts of two people. Once the winchman is safely aboard, obey his instructions and let him look after the casualty.

- If this is not the case act as follows: if you have to move the rescue device from the pick-up area to load the patient, unhook the cable and trail line from the rescue device and lay the loose hook on the deck so it can be retrieved by the helicopter. Never attach the loose hook or cable trail line to your vessel.

- When the patient is securely loaded (strapped in the stretcher face-up in a lifejacket if condition permits), signal the helicopter to move into position and lower the hook. After allowing the hook to ground on the vessel, re-attach the hook and trail line to the rescue device. Signal the winch operator with a “thumbs up” when you are ready for the winching to begin. As the rescue device is being retrieved, tend the trail line to prevent the device from swinging. When you reach the end of the trail line, gently toss it over the side.

- Prepare for high-line operation.

- When the winchman and the casualty are being lifted off, keep enough tension on the line to prevent swinging and do not cast the hi-line clear until told to do so.

In rough weather where it would be dangerous to use hi-lining the rescue could be done from a dinghy or even a liferaft towed behind the yacht connected with a long warp/painter of about 30 metres.

In the most extreme circumstances, such as abandoning the ship, you might be instructed to get into the water with a lifejacket. When directed by the rescue team, each crew member in turn is tied to a long warp and enters the water drifting astern to be retrieved.

Every Coast Guard helicopter has a trained swimmer, but the person is not a diver and may not go underwater unless they are trained as a diver and equipped with scuba gear. Diving under a capsized boat is dangerous work, especially with sailboats, whose rigging, lines, and sails can entangle swimmers.

Ship Rescue

A large ship in very rough seas will probably stop to windward of the yacht creating a smoother sea in the ship’s lee. It is generally dangerous for a yacht and its crew to come alongside another vessel. In rough seas, a lifeboat should be sent and come directly alongside.

- All crew to put on lifejackets