By Marcin Wojtyczka

62 minutes readCollection of procedures to use on a sailing boat.

Most of the issues on a sailing boat can usually be prevented by proper planning. Sir John Harvey-Jones, erstwhile chairman of ICI, once said, “Planning is an unnatural process; the nicest thing about not planning is that failure comes as a complete surprise rather than being preceded by a period of worry and doubt.”. But if the prevention fails, preparation needs to take over. So, make some prior thought and basic preparation before you head out to sea to keep the heart rate near normal and your crew safe.

Remember that in emergency situations, the crew of a vessel looks to their leader to determine their own level of anxiety. If the captain is prepared and projects a calm and confident attitude, the crew will be reassured and will remain effective. To manage the worst situations, you need to jump into immediate corrective action, not freeze up. Mental attitude is more important than even the most basic equipment. Your first action might not solve the problem, but you have to continue to try things until something does the trick. Think continually about and plan for contingencies: where are we going to go if the wind shifts and makes this anchorage or dock untenable? Which approach to this dock will give us the best options for getting off again? If we lose the engine, what sails should we have up to get safely away?

Man overboard

You should practice the procedure regularly with the crew but remember that your first and foremost priority should be to prevent it.

Prevention:

- Keep one hand for yourself, one hand for the shop.

- Ensure steady footing.

- Wear a life jacket and clip-on tether (lifeline) to a secure attachment point or a jackstay (in bad weather, at night, and whenever you feel unstable or want to).

- Don’t drink alcohol en route and be sober before you set out.

- Don’t dangle off the backstay or head for the leeward shrouds to have a pee, use heads.

Steps:

- Shout “Man Overboard”.

- Press the MOB button on the GPS and check that you have a track running.

- Toss buoyancy (e.g. lifering) and dan buoy.

- The person spotting the MOB point in the direction of the MOB.

- Immediately disengage the autopilot and crash tack (heave-to) to keep close to the MOB (before making the turn alert everyone to hold on; if running with the engine, stop the prop and turn toward the side the MOB went over).

- Send DSC distress alert and Mayday on channel 16, if you have any doubts that you can handle this.

- Check there are no lines overboard and start the engine.

- Make a recovery decision and prepare recovery equipment.

Final approach and retrieving:

- Drop the foresail(s).

- If the MOB is conscious, approach the MOB upwind (1-2 boat lengths) and toss a retrieving line (lifesling or floating heaving line with a bowline). Watch out for any lines in the water and disengage the propeller when in doubt. If under sails, approach with the mainsail and control the speed using the spill and fill method (let the main out until it depowers and then before you lose all way, pull it back again in to maintain steerage).

- If the MOB is unconscious approach closer to be able to reach the causality.

- Recover the MOB: pull the retrieving line to bring the MOB to the boat, tie a loop on the line (3-4 m up from the mob), attach a halyard to the loop and lift the mob onboard. Alternatively, tie a bowline at the end of the halyard and lasso the mob. An intermediate platform can be made with a rubber dinghy. A horizontal lift is preferred if possible, but in real life it’s very difficult to do if there are even the slightest waves. The simplest method might be to put a line around legs and have someone pull that line as you winch the person up to make sure the position is more horizontal.

- Apply first aid if required and call MRCC for medical advice.

MOB and prevention methods are described in great detail in this article.

Abandoning ship

The decision to abandon a ship is usually very difficult. In some instances, people have perished in their liferaft while their abandoned vessels managed to stay afloat. Other cases indicate that people waited too long to successfully get clear of a floundering boat.

Abandoning a ship should only be considered if your boat sinks or catches fire that cannot be controlled. Do not leave the yacht until it leaves you! Stay on board if there is no grave danger. Even a battered, damaged yacht will be a better shelter than a rubber raft.

Steps:

- (Captain) Announce abandoning the ship.

- All crew to put on all available waterproof clothing, don lifejackets and safety harnesses.

- Nominated person sends Mayday (DSC + R/T on VHF/MF/HF and/or Sat Com) and note present position.

- Nominated person exits with Grab Bag and be responsible for it.

- Nominated person collects other grab bag items previously agreed upon.

- Nominated person checks the presence of all crew and grab bags.

- Nominated person prepare(s) the liferaft for deployment (bring the life raft on deck and secure the painter).

- Nominated person deploy the life raft to leeward/downwind (in case of fire you may have to use the upwind side). Throw the liferaft overboard and pull the painter, kick sharply upon resistance.

- Nominated persons launch the dinghy and attach it to the liferaft (if time allows).

- All crew to enter the liferaft and pass grab bag(s). Step into the liferaft, do not jump. If impossible to step into, secure yourself to the painter and swim to the liferaft.

- Get to a safe distance from the vessel. Only cut the painter when the boat is actually sinking or there is a risk of explosion.

- Activate EPIRB (attach to a person or liferaft and put into the water to avoid strobe light and get better connection with the satellite), and activate SART Radar/AIS if vessels are expected in vicinity.

- Use VHF and other means of communication (e.g. sat com) and follow the distress procedure. Take seasickness pills. Inflate the raft floor. Keep warm and dry. Stream a sea anchor and arrange lookout watches. Arrange for collecting rainwater. Ration water, after 24h, to a maximum of half-litre per person per day, issued in small increments. Do not drink seawater or urine, this will only make you sick. Use flares only when there is a real chance of being seen.

The fact that on a cruising vessel, there may be only two people on board does not invalidate the necessity to have the above responsibilities clearly defined. A suggested sample of this is presented above, with the two crew shown as A and B.

Fire on board

Fire is an infrequent but terrifying occurrence on board a boat. Because of the environment and potential distances involved, firefighting assistance may take a while to arrive on the scene. Plus, unlike fires on shore, there may be no place to evacuate except into the water. It is important to make every effort to prevent fires. There are many potential causes of fire on board. Fire damage caused by flammable gases in the engine compartment is particularly common. Engine compartments on ships are usually closed systems, and vapours can quickly collect and compress here. Mixed with oxygen, a highly ignitable gas mixture can be formed.

Prevention:

- Fit smoke detectors with alarms.

- Inspect the electrical system regularly (the source of most boat fires).

- A clean boat is a safe boat. Keep electrical and mechanical areas clean and away from objects that could interfere with normal systems. This includes cleaning up any spilt oil (engine compartment, stove) or fuel.

- If you have gas onboard, turn it off at the source when not in use. Make sure the gas storage area is vented, and your saloon is fitted with a gas alarm serviced regularly. All crew should be trained to use the gas system. If gasoline or propane leaks into the bilge, the boat is a floating bomb ready to explode when the engine is started.

- Check for wear, damage, and leaks in burners, hoses, fittings, blowers and vents. A boat with a gasoline engine must have a bilge blower: one with a diesel engine should have one.

- Fit an automatic fire extinguisher system in the engine compartment, one large portable extinguisher near the stove and several portable extinguishers in living areas.

- Keep extinguishers charged and have them inspected as per the label. Twice a year turn the extinguishers upside down and shake them to loosen dry chemical.

- Don’t smoke onboard. If you must, make sure it’s on deck away from flammable items.

- Check and maintain all fire control equipment regularly.

- Make sure that the crew can escape from any part of the boat (e.g. a dinghy on the foredeck can make fast exit impossible).

Steps:

- Shout “Fire Fire Fire” and point at the location.

- Muster crew to deck whilst also allocating crew to extinguish the fire. Move to the windward side to avoid the smoke.

- Rescue people who may be trapped inside the boat. Keep as low as possible to stay away from dangerous smoke and heat. If someone’s clothes are on fire, help them get on the deck and roll them on the floor to keep flames away from face. Use a blanket to press out the fire, starting from the head.

- Meanwhile, if possible, immediately start extinguishing the fire, with available means: fire extinguisher, fire blanket, buckets of seawater (never on electrical or oil fire). Fires can double in size in less than 10 seconds, two minutes may well be the maximum time you have to put out a fire before it spreads through the boat. It’s not just the flames you should worry about. Older foam cushions give off hydrogen cyanide when burning – just a single lungful can kill. The quantity of the extinguishing agent is everything – a 2kg extinguisher will be twice as effective as 1kg so use everything you have available. Empty the entire content of the extinguisher in order to reduce the risk of reignition. If anyone on board has had any training then the likelihood of success is far greater.

- Pull the fire extinguisher pin, aim at the base of the fire, squeeze the trigger, and sweep the fire with a side-to-side motion. Aim well. You will only have 10-30 seconds before the extinguisher is discharged.

- While one crew member fights the fire, others should be preparing to abandon the ship by lanuching the liferaft.

- Call for help using any means: VHF CH 16, phone etc.

- After the fire is extinguished, carefully inspect the entire boat for embers at least twice.

Depending on the fire development:

- Isolate the fire by closing the ventilation system, skylights, doors etc.

- Isolate the fuel, gas and engine battery. Optionally throw all gas cylinders into the sea to avoid an explosion.

- If the engine does not have an automatic extinguishing system, try and discharge extinguishers into the engine space through a dedicated fireport, vent or hole. Do not open up the engine space.

- Steer the boat so that the fire does not spread (go into the wind if the fire broke out at the stern and downwind if the fire broke out at the bow).

- If the fire cannot be contained, call for help and abandon the ship upwind of the fire.

Water Alarm

Prevention is the best cure so make proper and regular monitoring of important components. This Pantaenius article describes this in detail.

Prevention:

- Check regularly: water-bearing fittings (hoses, clamps and valves, logger and sonar) - porous hoses and corroded clamps should be replaced, and the clamps should be tightened from time to time.

- The propeller and rudder axle seals are other openings straight into the sea. Find out how to service them and what the seal is made from: grease, oil or mechanical seals all need different type of care.

- Mount anti-siphon valves for bilge pumps and toilets to prevent water coming back into the boat if its outlet is underwater when sailing.

- Close seawater valves when you leave the boat in the marina.

- Lash tapered soft-wood plugs (bunks) to through-hull fittings, pipes and seacocks. In an emergency, you can drive the tapered end to plug a leak.

- Prepare the boat safety diagram to refresh your memory about where all through hulls are and check them.

- Have at least two big manual pumps (ideally diaphragm-type) and one movable.

- Keep spare material for makeshift repairs on board in an emergency (e.g. pre-drilled peice of plywood, epoxy, plugs etc.)

Steps:

- Alarm everyone that the ship is taking water.

- Make sure no one on board is seriously hurt. Make a DSC, PAN-PAN or SECURITE call on VHF. This can be cancelled later if assistance is not needed.

- Turn on all electric bilge pumps if not started automatically. If the engine is running you can use it as a very big pump. You can disconnect the raw cooling water intake of the engine and take the water hose from the through hull to empty the water. Be sure to check there is no debris that could hinder the water flow to the engine or it may overheat.

- Check if you are dealing with fresh or salt water (salt water usually indicates leakage in the hull, loose keel bolts, or leakage of the propeller shaft flange through stuffing boxes – they should leak only very slightly).

- Turn off all taps and valves (heads, restrooms, wash basins, water tank).

- Immediately start locating the source of the leak.

- If the hull is holed, heel it as far as you can in the other direction while preparing a patch.

- If the leak is small pump the bilges on a regular, frequent schedule so as not to be caught by surprise by a new leak. Keep track of regular log entries.

- If the water is coming through the deck, check the partners (the deck hole around the mast), window frames, and fastening for deck fittings, such as cleats.

- Plug the leak if possible. Depending on the hole size and location different methods might work:Lessen the water’s pressure on the breach by pushing something on to the breach – a cushion in a plastic bag, sail in a bag, sleeping bag, blanket, duffel bag with clothes held in place by a foot will work on a smaller crack to greatly reduce water ingress.Meanwhile, prepare a better fix: tapered plug, multipurpose waterproof adhesive, repair putty/epoxy, or plywood.You can also try fothering the leak from outside using a sail or collision mat stretched around the hull. The water pressure will help pushing it into the crack. A foil space blanket with tennis ball (or socks) can be made into a makeshift collision mat.

- Meanwhile, keep pumping and bailing with manual bilge pump(s) and other means (e.g. buckets, bailers, sponges, heads). Amongst these, a scared person with a bucket is the most efficient.

- You can also try to use a freshwater pump alongside the bilge pump. Keep the bilge free of small objects that might clog the pumps.

- If you cannot stop the flow or reduce it enough to safely get underway to a safe location, possibly to ground the boat on the shallows so it can’t sink, and prepare to abandon the ship.

Hole in the hull

Being holed below the waterline presents a number of problems in a variety of scenarios, depending on the size and location of the hole. It is possible to save the boat if you respond quickly. Just to give some perspective: a 5 cm hole 30 cm below the waterline will leak 300 litres per minute. A 10 cm hole at the same depth leaks 1100 litres per minute, enough to sink a 30ft yacht in 12 minutes.

- Tack the boat so that the hole is above the waterline (could help if the hole is near the waterline)

Options if you can get to the hole:

- Fothering the hole with whatever you can find to buy more time, e.g. stamp a pillow or cushion.

- Apply underwater epoxy repair kit (very effective).

- Lash plywood board from inside (e.g. engine room hatch with a sound-proofing sponge, floor boards, bunk board, bosuns chair):Screw the board (you might need to drill holes with a manual drill for underwater repair).

- Lash plywood board from outside:Push a loop of line out through the hole from inside the boat (e.g. with a coat hanger) and snag it on deck with boathook (hanging outside the boat not recommended).Insert a line through a pre-drilled board, knotting the end to hold it in place.Haul and tension the line from inside the boat.

Options if you cannot get into the whole:

- Fother a sail or use a purpose-made collision mat (wrapping it around the hull) – difficult to set up.

Porthole/Hatch failure

Breaking portholes or hatches might not flood your boat, but it could make your life on board hard.

Prevention:

- Close hatches on the sea: they can be thrown overboard by running rigging and can flood the boat in rough seas

- Avoid heavy weather if possible. If the vessel is knocked down or rolled it can cause hatches and portholes to be blown out due to wave pressure. The larger the area of the window, the greater the risk of failure particularly for many production vessels constructed from materials that are more susceptible to flexing under pressure

- Lash storm coverings to prevent windows from being compromised, both by heavy seas and loose items on the deck, such as flogging blocks and eyes

Options if it breaks:

- Tack the boat so that the broken porthole is above the waterline

- Lash something against the hole to minimize water ingress and buy more time (e.g. pillows, cushions, smaller sail, sleeping bags, blankets, duffel bags full of clothes)

- Lash plywood board from inside (e.g. engine room hatch with a sound-proofing sponge, floor boards, bunk board, bosuns chair):Drill holes in the hull and screw the board

- Lash plywood board from outside:Insert a line through a pre-drilled board, knotting the end to hold it in placeHaul and tension the line from inside the boat

Engine failure

Many engine failures at sea are caused by lack of maintenance, resulting in filter blockages, engine pump failures, overheating and then breakdown. It is worth remembering that one of the most common reasons for marine rescue service call-outs is for boats running out of fuel.

Prevention

- Keep the engine regularly maintained

- Always do engine checks before setting out

Daily in use:

- Check fuel, and crankcase oil levels (don’t rely 100% on gauges!)

- Look out for oil, fuel and coolant leaks

- Check fresh water coolant level

- Check that discharge of cooling water coming out from the exhaust pipe is rhythmic, and the gas is colourless and almost invisible

Weekly when in use:

- Check drive belts for wear and tightness

- Check gearbox oil level

- Check fuel racor filter for water and dirt. Drain off any contaminants until the fuel in the clear glass bowl is clear

- Check for water or sediment in the fuel tank. Drain off a sample from the bottom of the tank

- Check a raw water strainer and clear it if necessary

- Check battery electrolyte levels. Top up if low

Annually:

- Check cooling system anodes, replacing them as necessary

- Closely inspect all hoses for cracking or other signs of deterioration. Check all hose clips for tightness

- Check the air filter, wash or replace it as appropriate

- Check the exhaust elbow for corrosion. Ideally, you should detach the exhaust, so you can have a look inside

- Check engine mounts for deterioration. Look for loose fastenings and separation between rubber and metal components

- Check the shaft coupling and make sure all bolts are properly tightened

- Replace oil and oil filters every 100 to 150 operational hours or at the end of each season, whichever comes first

- Change gearbox oil every 150 hours or annually, whichever comes first

- Replace fuel filters every 300 hours

- Replace saildrive diaphragms after seven years

Winterising:

- Change the engine and gearbox lubrication oil, replacing any filters

- Darin the freshwater cooling system and refill it with a fresh solution of antifreeze

- Flush the raw water system through with fresh water if possible

- Check the raw water filter. Clean if necessary

- Remove the pump impeller. Pop it into a plastic bag and tie it to the keys, so you won’t forget to refit it

- Drain any water or sediment from the fuel tank and fill the tank if possible

- Also drain any contaminants from the pre-filter. Replace the filter elements

- If possible, squirt a little oil into the air intake and turn over the engine (don’t start it!) to distribute it over the cylinder walls. Some manufacturers recommend removing the injectors and introducing the oil that way – refitting the injectors once you have done so

- Change the air filter and stuff an oily rag into the intake. Do the same to the exhaust. Then hand a notice on the engine to remind you they are there!

- Relax and remove all belts

- Rinse out the anti-siphon valve with fresh water. Reassemble it if you’ve taken it apart

- Check the engine over thoroughly: engine mounts, hoses and their clamps (need to be tightened from time to time), exhaust and the exhaust elbow, and the electrical wiring

- Remove the batteries and charge them fully

Diagnostics and troubleshooting

Engine cannot crank at all:

- Low motor battery voltageSwitch to domestic batteries if they still hold the powerOlder engines can be started by opening the decompression level and cranking by handAnother trick employed by Vendee Globe champion Micheal Desjoyeaux is to wrap a line around the engine pulley at one end with the other end connected to the end of the boom. A quick gybe might have enough power to crank the engine

- Loose or corroded connections

- Battery switch is off, or defective

- Circuit breaker is tripped

- Solenoid or starter motors are defective

- Faulty key type switch

Engine surges or dies:

- Out of fuel. Either bad planning or fuel gauges are faulty

- Fuel cock shut – perhaps partially

- Blocked or partially blocked filters

- Fuel line blocked. Suspect the diesel bug!

- Water in the fuel

- Fuel lift pump defective – perhaps a split diaphragm

- Air in the fuel. Suspect a loose connection or leaking seal somewhereLearn how to bleed the fuel system if air gets into it

- Tank air vent crushed or blocked. There’s a partial vacuum in the tank

- Split fuel line

- Fouled prop

Shake, rattle and vibration of the engine:

- Bent prop shaft

- Damaged or fouled propeller. Prime suspects if the prop has recently been seriously fouled by flotsam. Possibly a lost blade, particularly likely with folding and feathering props

- Broken engine mount

- Loose shaft coupling

- Loose shaft anode

- Cutless bearing failure

- Gearbox failure. If so, you should be able to hear it if you can get close enough

- Internal engine failures, such as big end bearings, main bearings or valves. This should be clearly audible

Smoke signals – black or grey:

- Too much load on the engine. If black smoke emerges when moving from a standstill but clears very quickly, you may simply open the throttle too much.

- A dirty, weed hull will cause lots of extra drag. So will be towing another boat

- Thermostat is stuck closed, and the engine cannot cool down. As an emergency, you could remove it completely or better remove the valve’s moving parts (thermostat’s innards) and reassemble the housing (empty carcase)

- Too large or over-pitched prop. The engine is simply struggling to turn it

- A fouled prop. If the boat speed suddenly slows this is a very likely cause

- Dirty air filters. The engine isn’t breathing deeply enough

- Engine space ventilation has been reduced. Look for items that might be blocking the air’s path forward the engine

- Turbo failure – not enough air is getting into the cylinders

- Constriction of the exhaust system causing high back pressure. Perhaps a collapsed exhaust hose or a partially closed seacock

- Faulty injectors or injection pump

Smoke signals – blue:

- Thermostat is stuck open, and the engine is running too cool. The engine is running below its normal operating temperature. You have to replace the thermostat

- Worn valve guides

- Worn or seized piston rings

- Turbo oil seal failure. Lubricating oil is escaping into the hot exhaust gases

- Crankcase has been overfilled

- High crankcase pressure due to blocked breather

Smoke signals – white (should not persist for more than a few seconds, normal when the engine starts due to water vapour):

- Water in the fuel – most probable if the engine runs erratically

- Cracked cylinder head casting

- Blown head gasket. Cooling water is escaping from the galleries and entering a combustion chamber

- Cracked exhaust manifold

Overheating alarm sounds:

- Reduce the revs and check the exhaust outlet for raw water flow and stop the engine

If there is no or little water spurting from the exhaust it could be:

- Seacock partially or completely shutClose the seacockCheck that no objects (e.g. plastic bag) are obstructing the seacockRe-open the seacock

- Blocked, or partially blocked, raw water inlet or strainer

- Plastic bag over sail drive leg or seacock

- Air leaks in the strainer seal – the suction is being lost

- Damaged water pump impeller. Check the rubber impeller is slightly flexible, not hard, and replace it if necessary

- Split hose somewhere

But if there’s a good flow of water from the exhaust it could be:

- Thermostat failed in the closed position

- Loss of freshwater coolant. This could be a hose, the heat exchanger or even a calorifier

- Slack or broken drive belt. If the belt also drives the alternator, you would also expect the batter light or alarm to be activated

- Oil warning light or an alarm activated

- Shut the engine down immediately

- Check for engine oil leaks, crankcase oil level, pressure relief valve, defective sender unit or wiring

Alternator charge alarm sound:

- Stop the engine and investigate

- Broken or slack drive belt. If it’s also driving the raw water pump, the engine will rapidly overheat and the exhaust system could be seriously damaged by uncooled gases

- Defective alternator

- Power to alternator field coils interrupted

- Wiring fault or short circuit

- Glow plug remaining on (if fitted)

General lack of performance:

- Marine growths on hull or prop

- Damaged prop – possibly a bent blade

- Turbo failure or accumulated dirt

- Blockage to the fuel system. Check the pre-filter first to make sure it’s clear

- Cable not opening the throttle fully. It could be broken or frayed, or the holding clamp could have vibrated loose

- On stern drives and sail drives the propeller bush could be slipping

- Lack of engine pressure in the cylinders – the engine is in need of an overhaul

If you cannot repair the engine

- Sail to a marina where you can repair the engine or get it repaired

- In the right conditions and place, you could berth using sails alone, otherwise, send Pan Pan alert with VHF on channel 16 to get an assistance

Rig failure

Prevention:

Almost everything on board a yacht relies on the rig, and yet, often, it is not given the attention it deserves. Most rigging failures can be prevented by a careful inspection before passage and replacing rigging after five years or so of hard offshore use. The rigging is often neglected because of time pressure and lack of technical knowledge. The most common rig failure has been documented by Pantaenius.

- Inspect rig periodically (also underway) for damage and defects: yacht inspection checklist. It also makes sense to have a rig check carried out by a trusted rigger on a regular basis. Their trained eyes can detect potential faults or areas that could fail at an early stage

- Tune rig properly: step-by-step guide, sail and rig tuning book

- Plan passages to avoid bad weather and hurricane season. With modern forecasting, a true storm will rarely arrive unannounced, but as you venture further offshore the chances of being caught out increase.

- Avoid accidental/Chinese gybes as they damage the rig and bring it down. Tie a preventer line from the boom end (mid-boom is not as good) to a block at the bow or around a cleat and then back to a winch in the cockpit to tighten the preventer properly. Alternatively, use a boom break to slow the boom to a crawl. Make sure the kicking strap or boom vang is tight so the boom cannot lift and create slack for the boom to violently swing around.

Steps:

When a piece of standing rigging breaks, the first priority is to take the strain off the affected portion of the rig. But don’t reduce sails immediately, as the sails and halyards may be holding something up. Once the load is moved to the opposite side and reinforced, you can reduce sails. If a stay, shroud or spreader fails, but your mast is still standing, you may be able to use a halyard, topping lift or spare line to support your rig. This may buy you a little time while you secure the line and transfer the load. Useful backup is a roll of stainless-steel rig wire rope (or HMPE line), slightly longer than your longest stay and a compression terminal, such as Sta-lock that can be used to quickly fix a wire.

You may need to have tools and spare parts on board to fix rig failures. At a minimum, you should have tools to cut your rig loose and make minor repairs. The attached rigging spares checklist from Rigworks contains a comprehensive list of items that you might want to have on board. Before heading to sea, think through any other methods you could use to detach stays and shrouds other than cutting, for example removing pins, unscrewing bottle screws, removing a furler from the deck etc.

Protect the crew as much as possible. If the mast is going to come down there is less risk in having one person on deck than a full crew.

Dismasting (losing the mast)

- Ensure that the crew is safe. Put on a life jacket and harness.

- Designated person sends Pan Pan alert with VHF on channel 16. In case you lose your VHF aerial and radio communications, use a portable VHF or satellite phone.

- Check the boat for structural damage to ensure that you are not taking water. But don’t start the engine until the mast and any other wreckage are cleared to avoid fouling the prop.

- Get your liferaft and grab bags ready to deploy.

- Decide whether the mast can be safely secured to the boat or needs to be cut loose. If you are in rough conditions, and the mast is likely to sink the boat, don’t hesitate. Cut it loose (hacksaw with bi-metal blades – effective and cheap, hydraulic cutter or battery-powered angle grinder – effective but expensive).

- If you can safely save the mast, get a heavy-duty gloves and secure the mast tightly to the deck. Pad any contact points using fenders or bunk mattresses to minimize further damage to the boat.

- After clearing all lines from over the side, start the engine and motor to a port if you are within the motoring range. However, if you are outside the motoring range, you will have to set up a jury-rig with the remains of the broken mast or other spars like the boom or spinnaker pole. Keep a roll of 1x19 stainless-steel rig wire rope, slightly longer than your longest stay, for emergency stay/shroud construction. A 6mm HMPE line is a good alternative with even higher breaking strength.

Forestay failure

- Unless you have a strong inner forestay, you probably don’t have much time here. Warn your crew that the mast will probably come down

- Alter course downwind to reduce the load on the forestay

- Support the rig by setting up a jury forestay with a spinnaker halyard or spare line somewhere around the anchor fittings. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

- If the forestay failed at the base, you can try to reconnect

Backstay failure

- Head upwind immediately to reduce the load on the backstay

- If you have running backstays, tighten them up and reef the main sail below the point where the running backstays connect to the mast (the main sail will provide some support for the mast)

- Support the rig by setting up a jury backstay with a main halyard, topping lift or spare line. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

Shrouds or spreaders failure

- Quickly tack the boat and ease the load on your sails so that the failed components are on the leeward side and the load is reduced

- Support the rig by setting up a jury shroud with a halyard or spare line to the chain plate or turnbuckle. However, this is just to support the mast, you won’t be able to sail with it

Rig cutting options

- Hacksaws and multiple spare blades – highly effective on rod rigging

- High-quality bolt croppers – effective on Dyform, but not effective on rods

- Hydraulic bolt croppers – effective on Dyform and rods

- High-quality angle grinder – potentially useful for cutting rods and Dyform

- Sharp, deck–mounted safety knives

- High-quality scissors

Broken or lost halyard

- Make sure to always leave the topping lift loosely attached or have a boom strut that can support its weight. The mainsail is what holds the boom up under sail, so if the main halyard comes loose you have a potentially dangerous situation in the cockpit

- Get the boat hove to reduce the motion and minimise speed

- Take the sail down

- Go to the top of the mast to assess the situation – best done alongside in calm conditions

- If the line has not gone down into the mast, grab hold of it and bring it down. If it is still long enough, remake the halyard. If it is too short, reeve a new halyard to the end of it and keep pulling through

- If the line disappeared down the mast you have to get the reset the halyard. Lower a weighted thin messenger line down from the top of the mast until it is just past the exit gate for the halyard near the deck. The weight generally makes enough noise against the mast to hear where it’s currently at. Fish the messenger line out with a thin mousing wire shared into a hook to grab the line. Now pull the messenger line out of the gate and down to deck level. Now attach a new halyard to the messenger line and pull it through

Sail jammed on a furler

Sail jammed opened:

- Have a quick check with the binoculars that it is not a halyard wrap. If it’s not, the most likely scenario is that the sail opened too fast, or with not enough sheet tension, and the furling line is now jammed in the drum

- If it is safe to do so, open the drum and manually unwind the line, before re winding it. If this doesn’t help, there is likely a problem with bearings in the swivel or drum

- Lower the sail traditionally: unattach the tack from the furling drum and lower the sail with a halyard, pulling it out of the foil

- Inspect and repair it, if it is safe to do so

Sail jammed half open:

- Check to see the furling line is not jammed in the furling unit

- If the control line is too thick or too much is left on the furling drum, it’s possible for a jam to occur. Ideally, look to have three turns left on the drum when fully stored

- If the control line is not jammed, there are likely other issues such as seized swivel drum unit bearings or a halyard wrap. Wait for the wind to drop, remove the sheets, manually unwind the sail, drop it and find the cause of the issue

Sail jammed in between (not completely furled):

- Motor in circles to wrap the sail around the forestay and passing the sheets around the sail. If needed remove the sheets but be super careful. Lash with sail ties or rope where possible

- Alternatively, use a spare halyard to wrap around the sail

- If nothing works and the situation is getting out of control, cut the sail off

Halyard wrap around the forestay:

- Try opening up the sail again, depower it and let it luff a little to shake things loose. Then try refurling. You may need to do this multiple times to get the sail fully furled

- Lower the sail traditionally: unattach the tack from the furling drum and lower the sail with a halyard, pulling it out of the foil

- Find out the root cause and fix. Usually, it’s because the remaining halyard is too long or its lead angle to the swivel is too vertical (lead to the swivel should be at around 10-15°). A loose forestay can also cause wraps, so check tension. Make sure the furling control line heads into the drum at 90° to prevent riding turns (jam of the line)

In any case avoid using winch to furl the sail away! If the swivel is jammed, the furling line has riding turns or the bearings are gone, putting more force on the system will likely increase the problems.

Steering failure

Steering tends to be one of those things taken for granted until it no longer works. Many boats are abandoned each season due to failed steering systems because the skippers cannot make them head in the direction they need to go. Planning for steering problems involves two main pursuits. The first is inspecting and maintaining the steering system, and the second is planning for what to do should that system fail while underway.

You should regularly perform proper maintenance and inspections of a steering system before heading out to sea. Proper maintenance means mechanical inspection, tension tests and lubrication. Anyone with basic mechanical skills can do the maintenance, both quickly and relatively inexpensively:

- Comprehensive steering system inspection checklist

- Basic steering system inspection checlist (see “Inspect steering system” section).

Make sure you carry spares for your system as well. Having a few simple spare parts can make a big difference should a failure occur. For mechanical systems, make sure you have spares for items likely to wear and break such as the chain and cable. A few spare pulleys and clamps could be helpful as well. For hydraulic systems, make sure there is a good supply of fluid of the right type and a few spare hydraulic fittings

Steps:

Loss of control of the rudder

This may be due to a breakage in the steering linkage or the rudder breaking loose from the shaft and just spinning on the shaft.

- Engage autopilot. Autopilots ram is attached to the rudder post with its own tiller arm, so you can use autopilot for emergency steering

- Prepare emergency tiller in case of issues with the autopilot

Loss of the rudder

It is usually the result of the rudder shaft breaking and the rudder simply falling away. It is best to give this some thought while at the dock, put together a kit of parts to use when needed, and practice to make sure it works for you.

Methods:

- Set up a jury rudder (difficult but has been successfully used by many sailors). Most boats do not carry such a piece of gear aboard, so something will have to be fabricated and deployed while at sea. Use materials that may already be aboard that can be used to put together an emergency rudder (e.g. spinnaker or whisker pole, rudder head, plywood panels like small cabinet doors, or gangway). The emergency rudder should be about half the size of the original rudder to make it easier to deploy and use.

- Tow a drogue (e.g. Seabreak drogue) to pull on one side of the boat or the other in order to steer (has been successfully used by many sailors). If you do not have a drogue, even a stout bucket should work. Depending on the size of the drogue this may slow the boat down considerably and be inefficient if you have to go against wind and high waves

- Trim the sails to balance the boat (might only work on a limited range of headings and generally does not work well for most sailboats)

This Yachting Monthly article explores this topic in great detail.

This video is also worth watching to understand how to set up a drogue for emergency steering.

Jammed rudder

Probably the most difficult to deal with is the rudder becoming jammed and stuck in one position.

- Verify that the problem is not in the linkage or drive system: check that the autopilot is not holding the rudder over and gears in the lockers are not blocking moving parts of the steering. All it takes is a fender or dock line to jam a steering system

If it is clear that nothing inside the boat is blocking the travel, it will be that the rudder itself is stuck. It could be that the rudder jams against the hull or a result of something like a crab pot stuck in the rudder.

- Try to break the rudder loose by using the emergency tiller

- Dive to clear the rudder (only in calm see!)

Restricted / Poor visibility (fog, heavy rain, snow, …)

- Do not leave your berth, maybe unless you know there are only occasional patches forecasted

If you get caught out on the sea:

- Log a position and plot the fix on the chart when you see a sign of fog development

- Put on lifejackets (the decision whether to clip on is the skipper’s. You must take into account traffic density and the sea state)

- Gather the fog horn, hand bearing compass and flare pack

- Have the engine ready for immediate use (keep in mind the manoeuvrability vs noise trade-off)

- Raise your radar reflector if not permanently fitted

- Turn on your navigation lights to increase your visibility

- If you are motoring, keep the mainsail hoisted to increase your visibility. Avoid any complicated setup for the time being: spinnakers, cruising chutes, preventers and poling out headsails

- Have a liferaft, EPIRB or PLB ready to deploy

- Proceed at a safe speed (3-5 knots). Sailing too slowly can prolong the misery and makes any alterations of course less obvious on another vessel’s radar

- Keep a sharp look-out, using both sight and hearing (Rule 5 of COLREGs), and assign extra pair of eyes if possible

- Tune VHF to the relevant channel(s): Ch 16 when offshore as well as the local harbour or VTS channels when appropriate

- Use an echosounder, radar, GPS and AIS to build a picture of what is around. In the absence of radar, you will have to rely on GPS and “blind navigation” (based on depth, course, and speed) for pilotage into the harbour

- Sound required signals in restricted visibility as per Rule 35 of COLREGs with a fog horn or whistle (large ships only have a range of 2 miles, range of your signal will be even less!):If you only use sails: sound at intervals of not more than 2 minutes one prolonged blast followed by two short blastsIf you use the engine, and you make your way through the water: sound at intervals of not more than 2 minutes one prolonged blastIf you use the engine, but you are not making your way through the water: sound at intervals of no more than 2 minutes two prolonged blasts in succession with an interval of about 2 seconds between them

- Get the yacht into an area where the risk of collision is reduced, e.g. leave the shipping lane, find a bay to anchor to sit it out. Making landfall in fog is generally not advised due to the navigational dangers and the fact that the harbour may still be active with commercial vessels

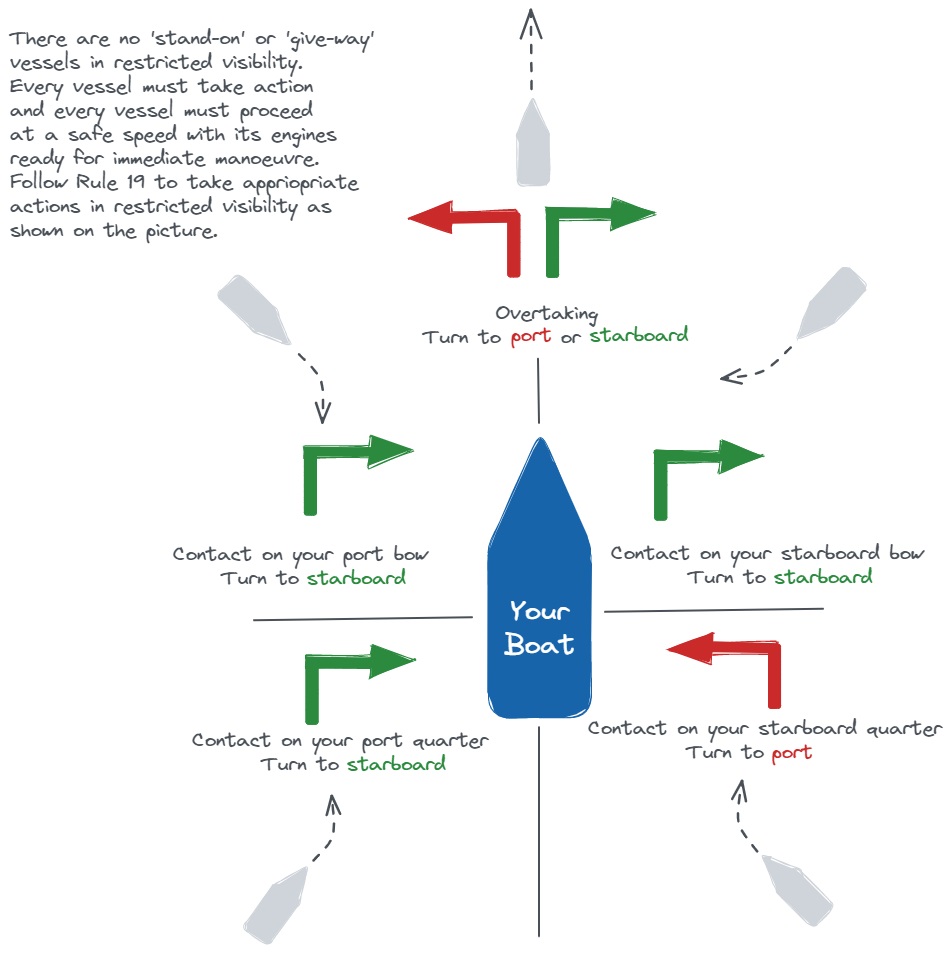

- Apply Rule 19 of COLREGs for conducting vessels in restricted visibility

Sails rip

Prevention

- Don’t let the sails and leech flog/flutter in the wind. If left too long, it can shred a whole sail in a matter of minutes. Flogging in the wind for half an hour may shorten the sail’s lifespan by months. Use leech line to trim tension of the leech to avoid flutter and adjust cars to keep pressure in the leech at the top of sail.

- Avoid chafe (e.g. pad spreaders and spreader ends with foam insulation when on longer crossings and tape patches of sail tape on the sail where it chafes against the spreaders, ensure there are no sharp pins on the turnbuckles).

- Reef according to wind/gust conditions (seams, clew rings, reef cringles and webbing put a lot of stress on the sailcloth and are most prone to rip in a squall).

- As soon as you have finished sailing, cover your sails to protect it from degradation caused by UV rays. Take off the sails after the season and do not leave them up when the boat is stored, whether in or out of the water.

- Reinforce any loose stitching immediately (“a stitch in time saves nine”).

Repair

- When a seam breaks, it could be temporarily solved by taking in a reef above the split if possible.

- If it is a roller furling sail, you should take it down rather than just furl it away, as furling a shredded sail can make it very difficult to unfurl again.

- Get the sail down (small tear may soon become a much bigger one).

- If too far from a sailmaker, make temporary repairs to the sail.

- Repairs to high load areas may require both patching and sewing:Remove old remnants of thread with scissors, flatten, clean with alcohol, align sides in tear, by putting smaller pieces of tape to line up the rip.Put a bigger patch and fold to reinforce the other side of the sail.Always round patches and start some centimetres outside the tear. Flatten the tape as you peel back off the backing, making sure no air bubbles form under the tape. After the patch has been attached, use the back side of a spoon (or similar) to press crinkles and air out. Even better, use a hot air gun, a hair dryer, the underside of hot kettle or similar, to make the glue bond properly.Large repairs can be done with non-sticky sailcloth can be glued with 3M, Sikaflex or similar.If necessary, use double-sided tape to keep panels together and reinforce with stiches. Put protective sticky-back tape over the new stitching.

Heavy weather

Preparation:

- Make a plan: assess your situation (shipping lanes, lee shore and shallows) and make a plan on how you want to ride the storm: escape to the port of refuge, steer downwind etc.

- Brief the crew: inform but do not frighten anyone, keep crew morale up, adjust watch rota if needed, take seasickness tablets, prepare warm clothes and stow any loose gear

- Clear the deck and stow it well: remove bimini, deflate dinghy, close all hatches, washboards, and lockers, cover all large windows with shutters or plastic coverings, fake lines

- Cook and eat a decent meal: make sure that everyone is well-fed and watered and that some food is prepared before the bad weather hits (e.g. sandwiches, hot water in thermos)

- Charge the batteries: may come in handy to start the engine or to run water pumps

- Double-check all safety gear

- Reef sails: reduce sails early, and hoist storm sails whilst you still can, and certainly before dark. The force on a sail varies directly with air density and the square of the wind speed. Cold air is denser than warm air and so creates a greater force (could be up to 30% or so). It’s important to appreciate that wind force does not increase in direct proportion to the wind speed, but rather in proportion to the square of the wind speed. A 40kt wind has 4 times the force of a 20kt wind (since 4040 is 4 times larger than 2020). Therefore, it does not push on the boat 2 times harder; it pushes 4 times harder.

- Rig a sea anchor or a drogue: if that is your storm tactic

Storm techniques:

1. Head for safe harbour if you can reach it before the bad weather hits

2. Avoid breaking waves if you can and keep the bow or stern oriented towards the seas

3. Steer downwind course (run before) if you have enough sea room, a competent helmsman or very good autopilot. This active storm tactic is suitable for modern lightweight boats with flat bottoms and wide beams.

4. Beat possibly with the assistance of the engine. Probably not sustainable in the long run because of fuel limitations and the stress on the engine itself from operating at extreme angles of the heel. But a viable option in coastal conditions and when you have to escape the lee shore

5. Heave-to if your boat can. This passive storm tactic can be suitable for traditional voyagers with long/full keel:

6. Forereach if you don’t have enough sea room and the sea is not breaking. This active storm tactic works by keeping the boat moving forward to windward (45-60 degrees to the wind) at low speed:

7. Lay ahull (only as a last resort):

6. Drop an anchor if you are blown into the lee shore and don’t have sea room

Storm techniques and preparation are described in great detail in this article.

Preparing the boat for a hurricane in the harbour:

- If possible, haul the boat. Put her as far away from the water and above the ground as possible to avoid the destructive effects of storm surge

- Otherwise, leave the boat at a well-protected floating pier that will rise with the surge

- Reduce windage: remove sails, sprayhood, bimini, sheets, snatch blocks, ventilators, lifesling, dinghy, deflate dinghy and stow it below or onshore etc.

- Close all through-hull fittings

- Set out as many fenders as you can find. To keep them in place, tie plastic bottles full of water (5L) to the bottom of each fender

- Double-up mooring and docking lines and their chafe protection. Leave a spare line in the cockpit so a Good Samaritan can help

- Get off the boat. There is little or nothing you can do on board at the height of a storm except endanger your life

Lightning

Lightning is the thing that scares most of us at sea. The only really preventative measure to avoid lightning is to sail in the opposite direction and hope for the best. Lightning can strike up to ten miles away from the cloud that generated it. Just because you are in the midst of a thunderstorm doesn’t mean you will get hit – there are many sailors who reported lightning striking the water next to their boat but not touching them. Others that were struck reported varying damage to electrical equipment and none experienced structural damage or fire.

The boat should ideally provide a direct route “to ground” down which the lightning may conduct to minimize damage. Most modern boats have the mast bonded to the keel by manufacturers. The masthead unit will definitely be destroyed when lightning hits a mast but with a lightning protection system the remaining electronics may survive. A high-tech solution is the Sertec CMCE system, which claims to reduce the probability of a lightning strike by 99% within the protected area. The system has been widely installed in airports, stadiums, hospitals and similar, but has now been adapted for small marine use.

Weather forecasts are still not particularly good at predicting thunderstorms with increased potential for lightning. In particular, they are not very reliable in terms of predicting the exact area.

Preparation

- Sound travel at a speed of 5 seconds a nautical mile. So when you see a lightning flash, start counting and divide the seconds by 5 to get the distance to the lightning (5 seconds = 1 mile, 15 seconds = 3 miles etc.). Thunderclaps can be heard for around 25 miles, so if the sky on the other side of the horizon is alive with light, but you cannot hear claps then the storm is still a way off. Keep moving but be vigilant

- Keep a 360° visual and radar look-out: due to the immense height of thunderclouds they are pushed along by the upper atmosphere wind, not the sea-level breeze. This makes it difficult to predict which way a cloud is moving. They can sneak up behind you while you are sailing upwind

- Reef to prepare for a squall: wind associated with thunderclouds can reach in excess of 40-90 knots in a matter of seconds, this will often be combined with torrential rain and drastically reduced visibility. The strong winds of a squall come with the rain. If the squall approaches without rain, the worst is yet to come. If it approaches already raining, the worst is past

- Unplug all masthead units, including wind instruments and VHF antennas and ensure ends of leads are kept apart to avoid arcing

- Put handheld or portable electronics (VHF, mobile phone, EPIRB, PLB, sat-com etc.) temporarily inside a metal oven. There is a theory that the oven on a yacht can act as a Faraday cage, protecting anything inside it from the effects of electrostatic discharge (ESD)

- As the storm gets turn off all electronics and use traditional dead reckoning navigation. The modern kit has increasingly efficient internal protection, but manufacturers still advise turning it off

- Turn on the engine. In case your batteries are fried, and you can’t use your sails you will be able to keep full control over your vessel

- Stay down below as much as possible

- Avoid touching metal around the boat, such as shrouds and guardrails. Areas such as the base of the mast, below the steering pedestal and near the engine have the highest risk of injury

Take into consideration that you should take protective measures also in the harbour and at anchor. If lightning strikes a utility pole the current travels down the electricity cable looking for ground. It can enter a vessel through the shore power line or can pass through the water and flash over to a yacht at anchor.

After the boat is struck

Expect masthead units, VHF antennas and lights to be destroyed, so make sure you carry a good quality spare VHF antenna.

- A nearby strike will be blindingly bright. Sit in the cockpit until your night vision returns

- If you or a crew member is hit, they could suffer from cardiac arrest - if so, reanimate immediately

- Check for any fires and put them out ASAP

- Make sure the bilge is dry and there are no holes in the hull

- If you have engine power, try to motor to safer waters

- Inspect the boat, e.g. main mast wiring, navigation lights, electronics, autopilot etc.

- Fluxgate compasses can lose calibration following a strike. Check all electronic compass readings with a handheld compass

- Call for help if needed and head to the nearest harbour. Until the boat had been lifted, inspected and checked below the waterline, you could not consider it seaworthy

Injury

The severity of sailing injuries can range from small cuts or scrapes to violent blows to the head or a crew overboard in frigid waters. Serious physical injuries involving broken bones or bleeding may need outside assistance. Once first aid is applied, the casualty should be made comfortable and Pan Pan Medico call made. This will result in the evacuation of the casualty by rescue services.

Try to anticipate situations before they become emergencies. Many situations can often be prevented. Get the boat under control, prevent any additional injuries or boat damage and try to reduce further risks.

Taking a First Aid/Medical care course (ideally marine focused) is a good investment of money and time especially if you plan ocean passages:

- RYA First Aid (1 day)

- MCA STCW Medical First Aid (4 days)

- MCA STCW Proficiency In Medical Care On Board Ship (5 days)

Steps:

- Stay calm but act swiftly. If you get hurt you will not be able to help others.

- Apply first aid if required.

- Make Pan Pan VHF call if you are experiencing an emergency that requires advice or assistance. Make Mayday call if there is an imminent danger.

- If you are Offshore use sat comm to get medical advice or assistance. If you are not subscribed to any telemedicine services (e.g. praxes, geos), call one of MRCC (Maritime Rescue Coordination Center).

You can subscribe to one of paid telemedicine services to get instant medical assistance offshore via sat comm, e.g. praxes. If you are looking for free options, you can get medical advice by calling International Radio Medical Center (CIRM) which has doctors available 24/7 (+39 0659290263). Another option is to call one of the MRCC (Marine Rescue Coordination Centre) that should be able to provide basic medical advice.

For example:

- MRCC Falmouth (UK): +44 01326317575; [email protected]

- International Radio Medical Center: [email protected], +39 0659290263

Helicopter evacuation

Helicopters are frequently used for search and rescue operations if the boat is within flying distance from the coast (150-400 NM). The helicopter rescue crew instructs on how to rescue the yacht’s crew or casualty and will try to communicate directly using marine VHF radio.

Steps:

- Clear all loose gear on the deck, or stow it below before the helicopter arrives. Unsecured covers, ropes, and even unstowed bits of clothing, are easily lifted by the down-draught of the helicopter rotors.

- Put on life jackets and harness.

- Do whatever you can to attract attention and signal your position: red hand-held flares (night or in bad visibility), orange smoke (daylight). If you do not have these, wave ensign or hi-vis life jacket. But do not fire parachute flares when the helicopter is closed by!

- If your engine is powerful and reliable, or if there’s very little wind, drop the mainsail and headsail. If you don’t trust your engine or are in any doubt about it, get ready to sail close-hauled on the port tack with the main sail up.

- Once VHF contact has been established, the helicopter pilot will give you instructions and outline intentions before reaching you. Closely follow any instructions you are given. Make sure that you understand them, it will be too noisy to hear your radio once the helicopter is overhead. The communication going forward will most likely be done on VHF 67 (UK), mobile phone and/or hand signals. If you have handheld VHF radio, use it. You won’t want to be down below, or going up and down the hatch. Make sure the rescuers know the extent of any injury or illness and what treatment has been administered.

- Steer absolutely straight in the direction the helicopter crew ask for. This will probably be upwind or close-hauled on the port tack, as fast as you can comfortably do. The wind speed from the rotor blades can reach hurricane force. The noise is so loud that you can no longer communicate by talking so additional instructions might be given by hand.

- When the helicopter is in position, a weighted line will be lowered first (hi-line method). Allow it to touch the boat or the water to discharge any static electricity then take up the slack and stow the loose end in a bucket to avoid snagging. Use gloves and do not tie the line to the boat!

- As the winchman is lowered on the wire, keep some tension on the line but only pull it in when told to do so - this may require the efforts of two people. Once the winchman is safely aboard, obey his instructions and let him look after the casualty.

- When the winchman and the casualty are being lifted off, keep enough tension on the line to prevent swinging and do not cast the hi-line clear until told to do so.

In conditions where it would be dangerous to use hi-lining the rescue could be done from a dinghy or even a liferaft towed behind the yacht connected with a long warp/painter of about 30 metres.

In the most extreme circumstances, such as abandoning the ship, you might be instructed to get into the water with a lifejacket. When directed by the rescue team, each crew member in turn is tied to a long warp and enters the water drifting astern to be retrieved.

Every Coast Guard helicopter has a trained swimmer, but the person is not a diver and may not go underwater unless they are trained as a diver and equipped with scuba gear. Diving under a capsized boat is dangerous work, especially with sailboats, whose rigging, lines, and sails can entangle swimmers.

Ship Rescue

A large ship in very rough seas will probably stop to windward of the yacht creating a smoother sea in the ship’s lee. It is generally dangerous for a yacht and its crew to come alongside another vessel. In rough seas, a lifeboat should be sent and come directly alongside.

- All crew to put on lifejackets

- Prepare and take a personal Grab Bag with you that should contain the most important items (bank cards, passport, ID, phone, keys, personal medications)

- Be ready to board the lifeboat quickly under instruction from the lifeboat crew

- In case you have to board directly, the ship’s crew will lower a ladder or a scrambling net over the side. If having to jump for a ladder or net, wait until the yacht crests a wave which lessens the danger of being crushed between the ship and the yacht

Running Aground

The Collision Regulations state you must maintain a proper lookout at all times. Paying attention at all times should help you avoid collisions and groundings. The regulations “apply to all vessels upon the high seas and in all waters connected therewith navigable by seagoing vessels”. The ‘Rules of the Road’ are contained in The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs).

Steps:

- Check for and help any injured crew member. All crew to put on lifejackets.

- Check the bilge for water and inspect the hull for damage. Check the rudder moves normally.

- Try getting out slowly by using the engine. Be careful when going in reverse as the rudder might break. Pushing yourself off the ground with a spinnaker pole or getting into the water might work on smaller boats given it is shallow enough. Alternatively, back the jib and push the bow down.

- If not effective, put out an anchor and wait for the tide to rise unless a strong onshore wind is blowing, in which case you must call for help.

- Try to heel the boat or spin her away from the shore by backing the jib, kedging off with a dinghy or taking the spinnaker halyard from the dinghy. To induce heel by sitting on a boom or leading the main halyard to an anchor or moored boat. Use everything soft on board to protect the hull from rocks or a reef (e.g. fenders, cushions).

- If needed use a PAN PAN call (or Mayday in case of imminent danger) on the VHF radio, advising the coastguard of your problem. Be wary in accepting offers of professional assistance to tow the boat off unless there is a need and an agreement has been made under insurance terms or a specified fee. As this is deemed to be salvage and maritime laws concerning salvage stipulate how much of the yacht’s value the salvage vessel can claim.

- Call your insurance company.

Towing

- Only request a tow if you really need it (last resort), e.g. running aground, leaking, entering a harbour with a broken engine or another emergency requiring that you get to shore quickly.

- To buy more time drop anchor if that is possible in the specific situation and location to keep the boat in place and allows time to plan the next steps. If the engine is broken, use the sails to get out of emergency situation. If it is not possible to set sail, ask incoming or departing boats for help. Alternatively, call the nearest marina or charter company and ask for towing assistance to avoid costs.

- Do not sign anything and do not commit to a salvage fee! If the situation is acute and the salvor insists on an agreement, choose the “Lloyds Open Form” contract (“no cure - no pay”). This open form of contract has international validity and can even be agreed by simple acclamation. Under no circumstances you should discuss specific amounts, talk about the value of the vessel or sign an agreement. Rather, you should contact your insurer as soon as possible and let the insurer negotiate. Private salvage companies often try to base their salvage fee on the value of the vessel rather than on their own efforts. More info on salvage issues can be found here.

- Alert nearby boaters (PAN-PAN message) to your situation as soon as possible and ask for help.

- Before getting underway, tell the tow how fast your boat will safely go, and, if she’s aground how deep into the bottom she’s imbedded. Agree on hand signals and VHF channel to be used to transmit instructions. If the other fellow appears to be careless or unseamanlike, you may decide to cast off the tow and fend for yourself.

- Handle towlines with the greatest care to avoid injuries.

- Attach the towline to the bow cleats. Do not tie it to the mast especially if it is stepped on deck.

- Keep the towline long so that the towed boat can ride easily in the through of a wave, not climbing up its back. If there is a swell when towing the boat, the length of the line should equal one wave period, so that both boats can steer up or down a wave at the same time.

- Steer carefully and use hand signals or the radio to communicate between the two boats.

- Keep the towline from rubbing against the headstay and the boat from wandering out to the sides of the wake.

Encountering orcas

Preparation:

If you plan to sail near the Iberian Peninsula known for Orcas’ interactions with boats, visit this website to get the latest recommendations and track encounters.

Safety protocol:

- Keep people away from the sides of the boat, ensuring they have the best possible protection against sudden movements of the vessel, falling into the water, or displaced loose items.

- It is always preferable to navigate under engine rather than sail. For sailing boats, stability may be affected if the keel is damaged, and it is therefore better to motor rather than sail.

- If you are in coastal areas avoid stopping the boat. Navigate in a straight line at the highest possible speed (within constraints of vessel and conditions) towards shallower water, if it is safe to do so, until the orcas lose interest. There are very few reports of interactions in water less than 20m. Also, the orcas will continue to attack the boat but, once separated from the main feeding group by 0.5 to 1 mile, they will give up the chase and return to the family unit.

- If you are further away from the shore, STOP the boat, turn off the engine and take down the sails. Disconnect autopilot to avoid damage and let the wheel/tiller run free if sea conditions and location allow it. The speed of the ship and the resistance of the rudder causes Orcas to persist in action. Stopping the movement, stopping the engine and letting go of the rudder causes them to drop their interest, ceasing the interaction, in most cases.

- Take hands off the steering wheel (do not touch it), and secure the boat for possible collision effects.

- Contact the authorities (by phone on 112 or by radio on VHF channel 16).

- If possible, turn off the echosounder, but leave other devices like VHF and GPS turned on.

- Keep a low profile on deck to minimise the interest to the orcas. Do not shout at the animals, do not touch them with anything or throw things at them, and do not let yourself be seen unnecessarily. But if you have a camera phone, or other device, record the animals especially their dorsal fins, to help identify them. All information of this sort should be sent by email to: [email protected] or reported via https://www.orcaiberica.org/en

- After the interaction ceases, wait for several minutes to allow the orcas to move away from the area before any interest is sparked by moving off.

- After a while check operation of the rudder, and if necessary, request assistance from the authorities through VHF channel 16 or phone 112.

- Make notes of the interaction, record the date/time and your position.

Risk factors:

- Depth of water: Stay in shallow water. There are very few reports of interactions in water less than 20m. There may also be a reduced risk within 2 miles of the shore and in less than 40m of water. Sailing close inshore may increase other navigational risks, especially in the event of boat damage.

- Antifoul: Possibly slightly higher risk with black antifoul, and lower with copper antifoul, but there is no statistically significant difference.

- Autopilot: The noise may increase the risk of an attack, but this is not yet proven. A strike on the rudder can also damage the autopilot.

- Day/night: Interactions happening both day and night, with only a marginally reduced risk seeming to be shown at night, but resultant rescue at night is harder. If you must pass through a danger area, then transit in daylight and under motor.

Deterrent measures:

- Reversing: Going backwards in the presence of orcas is considered illegal by certain authorities, except in the case of emergency, and is always illegal when there is intent to harm an orca. This method proved to be successful for some boats. If using this tactic, do so as soon as orcas are sighted rather than after contact is made.

- Sand: Orcas use echolocation to ‘see’ their surroundings, navigate and hunt. Some fishermen have been known to throw sand in the water to create a haze to disrupt the orcas’ echolocation ‘vision’. As long as the sand is not thrown at the orcas directly it is worthy of testing.

- Noise: The use of deterrent pingers is illegal without licence as it can cause hearing damage to the orcas, and can increase vessel-orca collisions. The few who have used it did not find it useful. Other noise on board has had mixed results.

- Playing dead: “playing dead” can calm the orcas’ heart rate. CA (Cruising Association) data shows that the interactions where crews followed the “playing dead” protocol lasted longer than those who did not. However, research undertaken by GTOA (Atlantic Orca Working Group) indicates that the level of damage to the yacht is marginally less when ignoring the orcas.

Action plan from Henry Buchanan, author of Atlantic Spain and Portugal

Good article about safety protocols here.

Collision

After a collision with another vessel that results in a major breach of the hull, you can do little more than deploy the life raft and get safely off the boat. Many newer boats are being designed with collision bulkheads that break the boat up into separate watertight compartments. The boats can stay afloat even if one or two compartments are flooded. Some boats are also filled with positive flotation that can inflate in contact with water.

- Check to see that everyone is still aboard and unharmed

- Pull up floorboards to determine if you are taking water

- If so, get all available bilge pumps working, locate and remove the water ingress

- Once the situation is stabilized, inspect the rest of the boat as rigging damage is common in collisions

- If the boat is sinking, call for help and abandon the ship

Line in the prop

Common obstructions include fishing nets, lobster pot lines, plastic bags or possibly even your own mooring lines. Your inboard engine may have an automatic security stop that will save the transmission or a line cutter on the shaft. First indication may be heavy clunking noises and/or violent vibrations. Most inboard engines will shut down themselves when obstructed.

- Identify the issue, if you cannot dive to check, use a waterproof action camera on a long stick (get some footage, review it and make a plan)

- If the weather is calm and the water warm, you can go down below with a serrated bread knife to cut the obstruction (wear gloves and preferably a helmet and watch out for any sharp growth on the hull)

- You can also try with the dinghy beside the boat. Stick your face in the water while wearing a dive mask, to see what you are doing. A boat hook with a taped and whipped-on serrated bread knife may do the trick.

- If you can get one end of the line, you can turn the gear in reverse, and use a combination of pulling and turning the gear. If the line is getting shorter, turn the shaft in the opposite direction. Be careful when testing to start the engine as it may have gone out of alignment or rubber engine mounts may have snapped.

- If you are in a marina, you can find a local diver to clear the prop for you. Expensive it may be, but definitely the safest.

Stuck anchor

- Use a tripping line whenever you anchor on a rocky/coral bottom, or in places known for debris. Attach a tripping line through the tripping hole, near the crown of the anchor. Attach a fender or dedicated buoy to the other end of the tripping line sure the line is longer than the depth of water. If you need to get the anchor unstuck pull the tripping line from an angle (possible from within a dinghy).

- If stuck in a mooring chain or electric cable on the bottom, it will be likely impossible for the windlass to pull it up. Use a short piece of chain that you let slip along the boat’s anchor chain to catch the shank. Then pull it out. Using a dinghy might get you a better leverage.

- If the water is clear, warm and not too deep you may be able to dive to unstuck the anchor.

- If another boat’s anchor rode or chain has been placed over yours, try lifting it up high enough so that you can pull your rode and then move it around the other boat’s rode.

- As a last resort, you may try to break the anchor using engine. However, this may damage the anchor and/or windlass as they are not designed for such extreme loads.

GPS fails / Blackout

- Make an immediate note of where you are, the speed and course in the logbook and paper chart.

- Get positions from a backup GPS, e.g. VHF with embedded GPS, USB GPS receiver that can be connected to a laptop

- Use terrestrial navigation in sight of land

- Use Dead Reckoning (DR) and celestial navigation offshore (you need to carry Sextant, Nautical Almanac and Sight Reduction tables)

- If you don’t have a sextant and required tables you can either rely on DR alone or use approximate methods for which you only need a stick (for keeping a constant latitude) and watch (to get longitude from noon sun)

Accident Report

- After an accident, assess damages and contact your insurer and/or boat owner

- In the event of a collision, you are required to stop and identify yourself, your vessel, your home port, your ports of origin and destination, and you are obligated to render assistance to people on board the other vessel, provided it can be done safely

- If there has been property damage as a result of your actions, and the damage appears to be over $1,000, or the seaworthiness of the vessel is affected, you are required by law to report the collision even if there are no injuries (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-a-marine-accident)

- In the event of a collision involving personal injury where the injuries require more than first aid treatment, you are required by law to report the collision to the local law enforcement agency

Additional resources

Yachting Monthly's video series of boat crash tests

Procedures to download

Emergency procedures in succinct format (PDF)

Fair Winds and Following Seas!

- Related articles:

- Seamanship

- Safety

- Boat Handling