By Marcin Wojtyczka

24 minutes readHeavy weather sailing preparation and tactics.

With modern forecasting, a true storm will rarely arrive unannounced, but as you venture further offshore the chances of being caught out increase.

Heavy or bad weather is a situation in which navigation for both the boat and its crew is hard. However, there is no strict definition of which conditions heavy weather occurs. It depends on the wind and wave conditions, sailing area (coast upwind, leeward), type of boat and people on board. As an example, heavy weather for small boats could start already at force 6 or 7, for larger boats this might be 8 or 9.

Many sailors fear storms as the greatest danger on the water, even though more emergencies and fatalities occur during times of relative calm. Nonetheless, strong winds and high waves can wreak havoc on a sailboat and any sailor should know how to stay safe in heavy weather.

How to avoid heavy weather

In today’s world of satellite communication and more accurate weather forecasts, it is certainly easier to avoid heavy weather than before. Sailing up a sea storm is very hard, sometimes impossible. That is why it is important to plan, execute and monitor passages properly, with a good weather forecast in your hands and an alternative strategy in your mind.

You should generally stay in the harbour if bad weather is predicted. But once you are out on the sea, far from a harbour, and the forecast predicts a deep low in your vicinity, you might not have enough time to avoid the system. You can attempt to escape as far away from the low as possible, and ensure that you are some distance away from any shelving seabed which could increase the likelihood of breaking waves. Breaking seas present a risk to all yachts no matter how good their stability rating is. This is due to the rotational power of the waves. This also applies to a following sea with breaking waves. In this case, the yacht can be flipped over end to end (pitchpoled).

Other than that, you should plan passages to avoid unfavourable seasons, e.g. hurricane season that can create Tropical Revolving Storms (TRS) that must be avoided at all costs (North Atlantic and North Pacific: July - November; Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea: June - November; South Pacific and South Indian Ocean: November - April).

Do not head out to sea if bad weather is predicted.

How to prepare for heavy weather

You should prepare the boat and the crew before the bad weather hits.

Navigation

Assess your situation and make a plan for how you want to ride the storm. Can you afford to run 200 NM downwind? Are you on a lee shore? Are there any shallows? Will this area be prone to breaking waves? Two classic storm strategies are to try to keep away from land, so you are not blown up on shore, and to sail away from the storm’s path - especially its dangerous semicircle. If you are near a lee shore or shallows, you need to get away from it as fast as possible and work out a tactic that will keep you off until the sea state has calmed down. You should also try to get away from a high concentration of traffic and shipping lanes.

Once you are caught by the heavy weather you should try to minimize your exposure to potential breaking wave conditions by exercising prudent routing and sailing efficiently to minimize time at sea. If you are caught in breaking waves, you should minimize the chance of being caught beam-on (you need to orient the boat bow into the waves or stern to the waves).

Ports of refuge

Check if there is a suitable port which you can pull into to escape or avoid heavy weather conditions. In most situations, making landfall in strong offshore winds (blowing toward shore) should be avoided as it might put you and the yacht at risk. But a large, sheltered harbour might be approachable before it gets too bad.

Brief the crew

Inform the crew that harder conditions are expected but do not frighten anyone. Adjust the watch rota if needed. The crew should take seasickness tables, prepare warm clothes and stow their gear.

Clear everything on and below deck

Take everything below (including the dinghy) and stow it well. Make sure all running rigging is well stowed, so no lines are going to go overboard and foul the propeller. Make sure that all furling sails cannot unfurl by themselves (wrap sheets around the sail 3 or 4 times, cleat off the furling line, and secure the drum, so the sail cannot come unwrapped). Remove the bimini and deflate the dinghy. Ensure that all hatches and lockers are closed. Put away extra clothing, books and so on. Put away all dishes, pots, pans and so on. Leave nothing on the gimballed stove. Make sure all knives are in an enclosed drawer. Leave the stove gimballed, but if it can swing far enough to hit the safety bar in front of it, wrap the bar with a towel to protect the glass in the oven door.

Rest well, cook and eat a decent meal

Make sure that everyone is well rested, fed and watered and that you have some food prepared for the expected duration of the heavy weather (e.g. sandwiches, tea in a thermos). This is critical to prevent fatigue (especially if the crew is shorthanded) and be able to steer the boat relative to the waves throughout the storm.

Charge the batteries

You should have batteries charged in case you have to start the engine or use water pumps.

Double-check all safety gear

Ensure that the safety equipment is ready (EPIRB, PLB, PFDS and harness, VHF, Grab Bag, first aid kit etc.). This should generally be already checked as part of the passage prep, but it will not harm double-checking.

Reef sails

Reduce sails early and hoist storm sails (if you have one) whilst you still can, and certainly before dark. The force on a sail varies directly with air density and the square of the wind speed. Cold air is denser than warm air and so creates a greater force (could be up to 30% or so). It’s important to appreciate that wind force does not increase in direct proportion to the wind speed, but rather in proportion to the square of the wind speed. A 40kt wind has 4 times the force of a 20kt wind (since 4040 is 4 times larger than 2020). Therefore, it does not push on the boat 2 times harder; it pushes 4 times harder.

Prepare storm devices and hank on storm sails

Be ready to fly the storm sails. Put warps, drogue, sea anchor, chafe gear, or other devices for storm tactics on the top of the cockpit locker or on the cabin sole in a place where they can be easily reached.

Make the boat watertight

Secure all hatches and ports, and put hatchboards in. Check the main bilge pump and emergency pumps. Pump the bilge dry. Cover any air vents.

You can also find this video by Skip Novak very informative.

How to cope with heavy weather

There are several proven storm tactics, all of which aim to reduce the strain and motion by pointing one of the boat’s ends (either bow or stern) toward the waves. No one tactic will work best for all boats in all conditions, so you have to practice and work out a strategy that works best for you and your boat and be ready to implement a variety of tactics.

Don’t go especially if you expect breaking wave conditions

If conditions are wrong or are forecast to worsen, don’t go. If you can avoid the storm, then do so. Stay in the harbour and enjoy time with your shipmates. Make sure your anchor or mooring lines are secure, read a book or brush up on some sailing knowledge with your crew (e.g. COLREGs, navigation).

If your boat is threatened by a hurricane, strip all excess gear from the deck, double up or redouble all docking or mooring lines, protect those lines from chafing, and get off. Do not risk your life to save your boat.

Head for safe harbour

When the heavy weather begins or is predicted, the first impulse is often to drop the sails, start up the motor and head for land. If you can safely reach a harbour, this may be your safest option. The danger lies in being caught in the storm, close to shore, with no room to manoeuvre or run off. The wind and waves can rapidly turn shallow areas or narrow channels into a more dangerous place than open water, especially if the storm will be short-lived, and it’s mostly a matter of waiting it out. Waves become steeper and more likely to break in shallow areas, making it difficult to control the boat. Also, consider the risks if your engine were to die and the wind rapidly blow you onto the shore. You may have better options staying in open water and riding out the storm.

Keep the bow or stern oriented toward the seas

In heavy weather, the most common reason for a capsize is a breaking wave on the beam. Don’t beam reach when wave heights equal or exceed the beam of the boat and don’t lie beam-to the seas in breaking waves. Try to balance the boat for the wind angle you want to maintain, e.g. use mainsail for going to windward, and headsail when running off.

Steer downwind course (running off)

Active steering downwind course is probably the best technique for a modern lightweight boat as long as you have plenty of sea room and a competent helmsman. If the stern is not kept perpendicular to approaching waves, a wave can push the stern around to one side, causing a broach and capsize.

Advantages of running off:

- Reduction in apparent wind speed eases the strain on the boat’s equipment

- Steerageway is maintained, so the helmsman can avoid a particularly bad wave

- If the crew is not able to steer manually the boat is likely to manage on her own with autopilot able to handle the steering as long as the waves are not breaking

Disadvantages of running off:

- Lots of strain on the boat. Big ships and long keel boats like fisherman boats prefer to take big waves on the bow, but there are serious forces in play and modern lightweight performance yachts are better off going with the wind and waves rather than fighting against the nature

- The yacht might pitchpole as it accelerates down the waves and hit the waves in front. Streaming warps or a drogue with bridle might be necessary

- Useful if it sends you in the right direction, but perhaps not very good if it puts you far from your destination

- You will also stay in bad weather for longer, rather than letting it pass over you

- Having someone on deck helming puts them in a vulnerable position with potential waves landing on the deck

- Need a lot of sea room. Most depressions are fast-moving and usually wind down after 1-2 days. With an average boat speed of 5 knots, you will need a minimum of 120 nautical miles of sea room

When surfing the waves at some point you might have to slow the boat down to be able to control it. The sail plan would mainly depend on your boat and available sails on board. For a typical cruiser, this could mean a main sail with a second or third reef and reduced headsail (rolled or storm jib). You can also drop the main sail or use a fourth reef.

When running it is necessary to keep the yacht at right angles to the seas. Therefore, it is advantageous to set the sails as far ahead as possible and to take off the main thus improving the capability of steering because the distance between “centre of effort of the sails” and “centre of effort of the rudder” is enlarged.

In extreme cases, where even a scrap of a sail is too much, you may need to drop all the sails and simply run under bare poles. In true storm conditions, the resistance of the mast, hull, and rigging will drive most boats at 4 to 5 knots. A staysail sheeted flat amidships can help keep the boat tracking downwind.

Be wary though that if you run free and the boat starts surfing regularly, you may be knockdown. In the Queen’s Birthday Storm, three boats ran free. One was rolled and dismasted, one was knocked down past 90 degrees and dismasted, and the third deployed a speed-limiting drogue off the stern and was fine. Some sort of drag device can help keep the boat upright in survival storms. Drag devices can slow the boat down and orient its bow or stern into the waves reducing the chances of getting knocked down and rolled. That being said, some very experienced sailors have found that the boat did better when they got rid of the drogues they were towing and ran free. In the classical text passage, this is how Bernhard Moitessier described it: “Now she is running bare poles, free, heeling, when the sea is running up at an angle of 15 to 20 degrees, is accelerating like a surfer … and is responding to the helm when I bring her back downwind”.

Beat possibly by the assistance of the engine

If you lose too much ground to leeward you can try to beat to windward with a reefed mainsail and the engine. Relying on the engine in an offshore storm will probably not be sustainable in the long run because of:

- fuel limitations

- stress on the engine itself from operating at extreme angles of the heel (engine not lubricating correctly and overheating)

- rough seas can stir debris in the fuel tank, clogging fuel filters, and stopping the engine at a potentially very unsuitable time

- in a following sea, water can back-fill the exhaust and flood the engine if the exhaust is not high enough.

- accidental flooding can also occur if the engine cooling water anit-syphon becomes blocked

Nevertheless, this remains a viable option in coastal conditions when dealing with a passing squall.

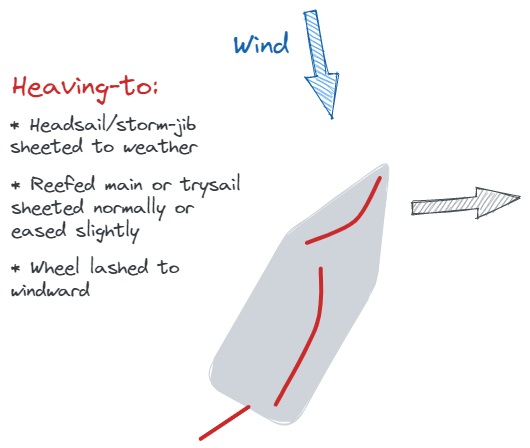

Heave-to (if your boat can, practically suitable only for traditional voyagers)

Heave-to under reduced sails with a staysail or jib sheeted to windward and the helm lashed over to maintain a heading of approximately 45 degrees off the wind.

Heaving-to gives the crew a rest, and it can be a safer means of riding out a storm rather than trying to sail it out, but you need the right boat for this (see below). It is a classic survival technique where you tack the boat through the wind, leaving the sails backed, and the wheel lashed to windward. Locking the rudder with a stretchy line is the best because it holds but also gives slightly to avoid extreme tension. Note that in a strong wind, it might be dangerous or impossible to tack the boat, so you should rather back the headsail to windward by trimming the windward sheet.

Heaving-to stabilizes the boat and slows down the drift to 2-3 knots on average. The leeway a boat makes while hove-to means that you need a sea room. In offshore gale conditions, most boats will drift 20-50 miles to leeward every 24 hours.

You should be able to adjust the sails to sit at about 45-60 degrees off the wind. Finding the right balance where a boat will sit comfortably at the correct angle to the wind and not give up too much ground to leeward will require some adjustments. You should lower or deeply reef the main or raise a storm trysail (very small storm mainsail) as well as a small headsail (storm jib) to reduce loads on the rig. Depending on how the boat is pointing to the wind and waves you might need to drop the headsail or the mainsail.

A really cool part of heaving-to is that the boat will leave a wake to windward. Breaking waves hit this “slick” and flatten out, thus reducing the wave action on the vessel.

Modern boats generally do not heave-to very well, and certainly not as well as a solidly built full-keel boat will. The sail plan and hull geometries of modern designs just do not let the boats lie stable to the wind. You need to experiment with your boat and see how the boat behaves. This tactic will be effective in moderate seas. The danger arises when the swell picks up and starts to break. This might leave the yacht beam onto the prevailing seas.

Steps:

- Back the headsail to windward by trimming the windward sheet. If you have a big headsail, roll it up to handkerchief size or set up a storm jib. Do not gybe because the boat might fly down a wave and tacking might be impossible

- Reef and ease the mainsail until the boat stops all forward motion

- Put your rudder over hard to windward, taking care that the boat does not go head to wind. Lash the helm well, so it can’t work

- Play with the mainsail trim until a balance is struck at a good angle to wind and waves. The ride should be comfortable. It’s all about a balance between what is below the waterline (keel and rudder) and windage above (sails and rig)

- If there is still too much tendency to climb to windward, drop the mainsail. This would probably be the case if you had a third reef, which would be too much sail. A fourth reef (storm trysail size) might work

- Keep a close eye on the boat for some time to make sure it stays in balance during various cycles of wave and swell patterns

- Crew can go below. One watchkeeper is sufficient, booted and suited to go on deck to make any changes

Heave-to earlier rather than later. It is much easier to set up everything in a controlled situation. If the wind is rising, there is no point waiting as you will not lose much distance anyway.

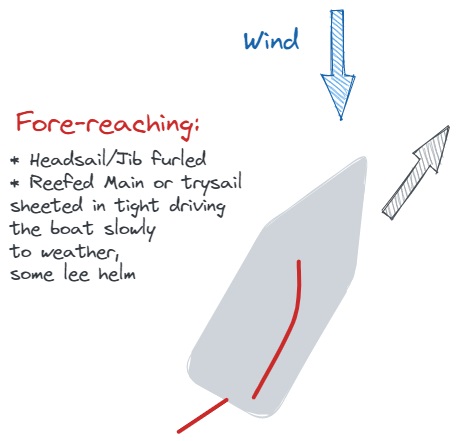

Forereach

Another technique akin to heaving-to is forereaching. Forereaching essentially keeps a boat moving forward to windward (off the wind at 45 to 60 degrees) at greatly reduced speed and is accomplished by sheeting the jib amidships (not quite backed) or lowering it all together, with the reefed mainsail sheeted in tight and the helm lashed slightly to leeward with stretchy line. Think of it as sailing your boat very inefficiently to windward. Often a boat that is improperly hove-to ends up forereaching unintentionally. Most boats will foreach comfortably into gale-force winds under a double-reefed mainsail. A triple-reefed mainsail or trysail will keep the boat pointed into the wind and moving forward on sloops. A staysail may work better on a cutter.

Forereaching can be a better alternative to heaving-to in certain situations. In tidal areas, for example, forereaching can be used to slow down a boat without losing ground to an outgoing tide or current. Forereaching allows you to continue to make slow miles toward your destination without beating up the boat and yourself. If you are just trying to slow down the boat and cannot afford to make leeway, forereaching makes a lot of sense.

Forereaching is a perfectly acceptable storm tactic as long as the waves are not breaking or dangerously confused. This is because large breaking waves will try to push the bow off and expose the side of the boat to the sea. If the boat is becalmed in the trough, it will fall off the wind before the next wave arrives and could get it beam-on. Because of the slow boat speed, you might not be able to head up fast enough. In a dangerously confused sea, a wave may strike the opposite side and force the boat to tack through. She might also tack inadvertently if the wind increases enough to overpower the rudder and bring her head through the wind. From down below you should be able to assess and tell if you are reaching the limits of forereaching as a storm tactic if the boat tacks or if waves are knocking the bow off repeatedly and interrupting the windward motion.

To effectively and safely forereach in storm conditions you need a boat prepared for offshore sailing. Your boat needs to be able to take waves on the bow and lots of loads. Sturdy boats with long keels will be better for taking big waves on the bow than modern lightweight performance yachts which are generally better off going with the wind and waves.

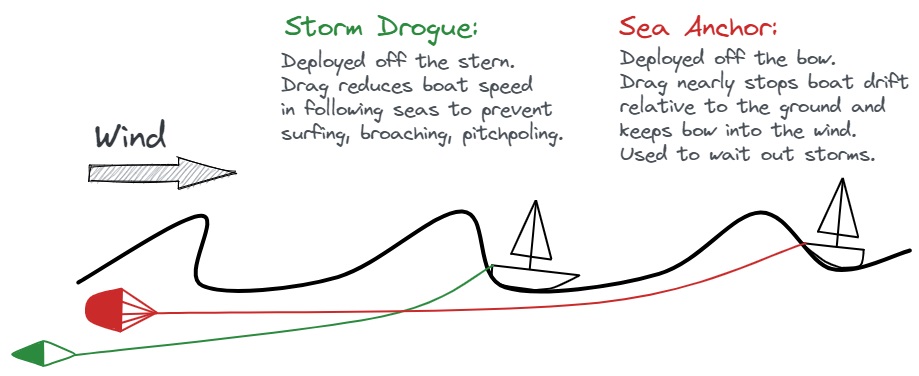

Lay a drogue astern

Even if running under bare poles you have too much speed, there are several possibilities to decrease the speed to avoid pitch poling or broaching, e.g. using warps (bight of the line will trail behind the boat 300 feet or so), a chain with anchor, or deploying a drogue. You should practice using drogue before in various conditions. These are difficult-to-handle devices and the load generated by them is enormous. Theoretically, speed-limiting drogues should be deployed two waves back to keep it from being jerked out of the face of the wave as the boat accelerates toward the trough. But once you deploy it, the tensions will likely be too big for you to be able to adjust anything.

Studies over the last years have shown that drag devices help stabilize a boat in survival conditions. Waves tend to be steep and break early in the storm. This is because the underlying water is not yet moving at speed with the wind. During that period, drogues or towing other objects like warps stabilize the boat. After the storm winds have been blowing for 48 hours or more, the waves become less steep, but their velocity increases considerably. Drag devices may then slow the boat too much in front of the fast-moving waves. Cutting the drag devices away may allow the boat to rise up and go over the waves more smoothly, but only if the boat is hand steered to avoid breaking seas. This situation is most likely to occur in the Southern Ocean where fully developed seas are more frequent.

If you do plan to use a drogue, deploy it before the bad weather hits. Amongst drogues the Jordan Series Drogue receives a lot of praise from long-distance sailors. A more conventional and solid drogue should do it as well (e.g. Seabrake Drogue).

Lay ahull

If things get very bad, the last resort might be lying ahull: drop all the sails, fix the tiller to leeward and lock oneself inside the boat, allowing the boat to drift, completely at the mercy of the storm. The ride will not be comfortable, and the boat may not make it, but it is an option when there are no others left. This technique is best suited to heavy displacement yachts with excellent stability characteristics. Light, modern boats will often lie abeam big seas which are very prone to roll. Damage to the boat is likely. Of the three boats that lay ahull during the infamous Queen’s Birthday Storm, only one, a catamaran, remained upright. The other two were both rolled and dismasted.

Many experienced ocean sailors are of the belief that once it has got into severe gale conditions the crew should all be below deck, with the boat potentially sitting to a drogue or sea anchor from the bow and the hatches battened down. Indeed, many of the injuries sustained during the 1979 Fastnet race were from people trying to helm or move around the boat.

Drop an anchor

If you have in the vicinity of a shallow water, and you have no other option to escape the lee shore you can drop an anchor as a last resort. Requirement: 30 - 50 m of chain, plus nylon cable of the same length (or both longer). A cable of nylon is elastic, and it is able to absorb the movements back and forth.

My roadmap for cruising on a modern performance boat

Up to Beaufort 4

- Full sails

- Maintain the course

Beaufort 5

- I reef in the main (or rolled-in)

- Maintain the course

Beaufort 6

- 2nd reef in the main (or rolled-in)

- Reduced headsail

- Maintain the course

Beaufort 7 and up to a wave height which roughly matches the beam of the ship

- 2nd or 3rd reef in the main (or rolled-in)

- Running: further reduced headsail

- Upwind course: storm jib

- Maintain the course

Beaufort 8

- Important not to sail beam-on to the seas especially if the sea is confused or breaking, switch to running (vessel oriented with the stern into the waves) or to beating (with the bow into the waves)

- Using the self-steering as long as possible with somebody near the helm, who takes the wheel if necessary or forereaching with a wheel lashed with a stretchy line

- Upwind course:

- 3rd reef in the main (or rolled-in)

- storm jib

- with additional support from the engine if needed

- Running:

- main with 3rd reef (or rolled-in) and storm jib

- or storm jib only to avoid broaching

Beaufort 9

Upwind course

- main only, 3rd reef (or rolled-in) or storm trysail

- steering manually or forereaching

- with additional support from the engine if needed

- as long as the sea permits

Running

- under storm jib solely

Beaufort 10 and more

- Running under small storm jib only or bare pole

- Maybe with a drogue or towing warps to reduce speed and keep the stern held down

- Retreat of the crew into the ship, close off the vessel

- Reporting the position on VHF if near a busy area: “Restricted in manoeuvrability”

- Stay with the boat as long as the boat floats

Golden rules of heavy-weather

- If you can, don’t go if heavy-weather is predicted.

- Keep clear of any potential lee shore.

- Avoid areas prone to breaking waves (e.g. shallowing shore, sea mounts, harbour bars on ebb and swell, headlands).

- Prepare the boat and crew before the heavy-weather hits.

- Don’t beam reach when wave heights equal or exceed the beam of the boat, especially in breaking sea.

- Reef early. Don’t be caught over-canvassed.

- Balance the sail plan for the wind angle you want to maintain.

- Don’t leave the boat until the boat leaves you.

- Get underway once conditions moderate.

- There is no one right way of handling storm at sea. There is only what works for different boats and their captains in different storms.

Other tips

- Don’t lie ahull in a monohull unless there are no other options left. This tactic is most likely to result in knockdowns, rolls, and dismasting.

- Running free is likely to result in a knockdown in survival conditions when the boat starts surfing regularly.

- Some sort of drag device (e.g. drogue, warps, anchor) can help keep the boat a survival storm by making sure the boat is oriented with the bow or stern into the seas.

- Having-to does not seem like a successful strategy for modern performance boats.

- There is no “silver bullet”. Keep trying different tactics until the boat feels “right” in the given conditions.

- Keep the relevant amount of sail area for the conditions. Carrying too little sail means the boat will be sluggish and unresponsive allowing her to end up beam-to the seas. You will also stay longer in the storm.

- Get underway once conditions moderate. Most knockdowns and capsizes happen near the end of a storm, after the wind has shifted causing the waves to become more confused. Getting some sail back up at the end of a storm is the best way to stabilize the boat and deal with the dangerous sea state.

- If the boat speed drops to 50% of the hull speed, the boat is under-canvased and needs more sail area to drive through the waves, even if that means sailing at a higher angle of the heel than normal. Hull speed in knots equals 1.34 times the square root of the waterline length in feet.

- Don’t leave the boat until the boat leaves you. It has been well documented in sailing disasters such as the 1979 Fastnet, the 1998 Sydney-to-Hobart Race, and the 1994 South Pacific Queen’s Birthday Storm that you should not abandon a vessel until it is literally sinking beneath your feet, and you have to step up off the deck to your raft. The boat is the safest place to be almost all the time, and staying with it increases your chances of survival. Case after case, crews have been injured or killed in a liferaft, while their abandoned vessels have been found weeks later floating happily on their own.

- Clip on the harness whenever the conditions deteriorate, or you feel uncomfortable.

- When climbing to the crest of an unusually large, steep wave, head up and then bear away to slide down the boat at an angle of 60-70 degrees to the wave to keep the boat from free-falling or burying its bow in the trough. A similar approach can be used when running off

You and the storm

Few people get to experience the full fury of a storm. Although everyone will remember it differently years later, a long, wet, cold sail through a storm can be miserable. It is memorable but not pleasant so do not dream about it. As a skipper, keep calm and make the best of it. Watch over your crew, offer help to those who need it, and speak a few words of encouragement like “This is miserable, but it will end”.

Additional resources

- Skip Novak's storm sailing techniques.

- Essential boathandling skills in heavy weather.

- Using a drogue.

Happy Sailing!

- Related articles:

- Seamanship

- Safety

- Boat Handling